Through her sculpture, writing, and filmmaking, Olivia Erlanger examines how architecture frames American dreams and delusions.

Her exhibition of three new sculptures, Split-level Paradise, reflects upon the infatuation with home ownership in the US. The title refers to a style of home with staggered floor levels, which gained popularity in the years following World War II as suburbs expanded. Drawing from a wide breadth of research, Erlanger sees the marketed dream of homeownership as inextricably linked to the gender oppression of the “housewife” and a geographical pattern of racial discrimination otherwise known as red-lining. She also points to the economic crash of 2007-08, when a trillion dollars of dud mortgages blew up the financial system, and the hopes of the so-called American middle class. Erlanger’s latest body of work asks if the dream is coming to an end; moreover, was it ever real to begin with?

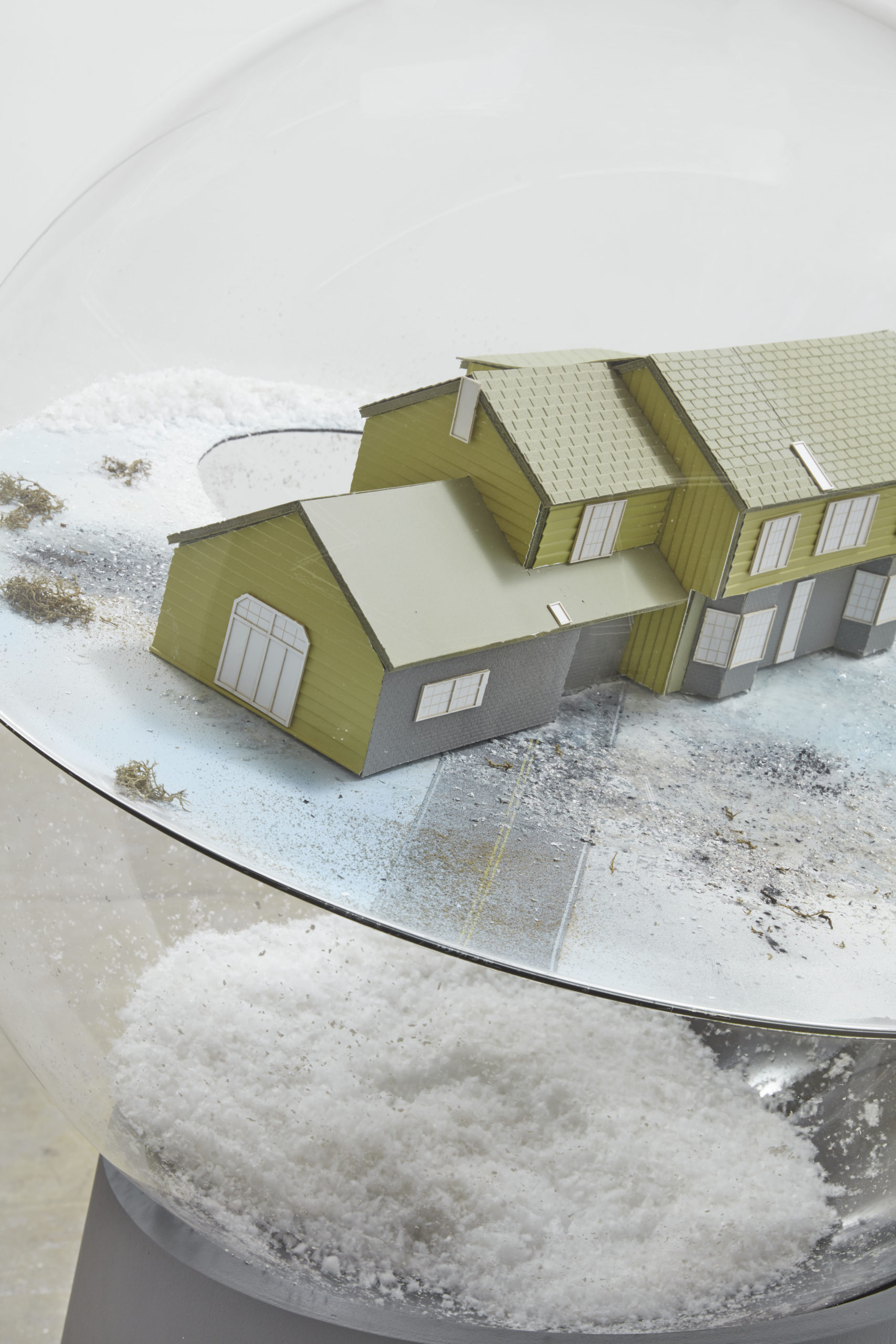

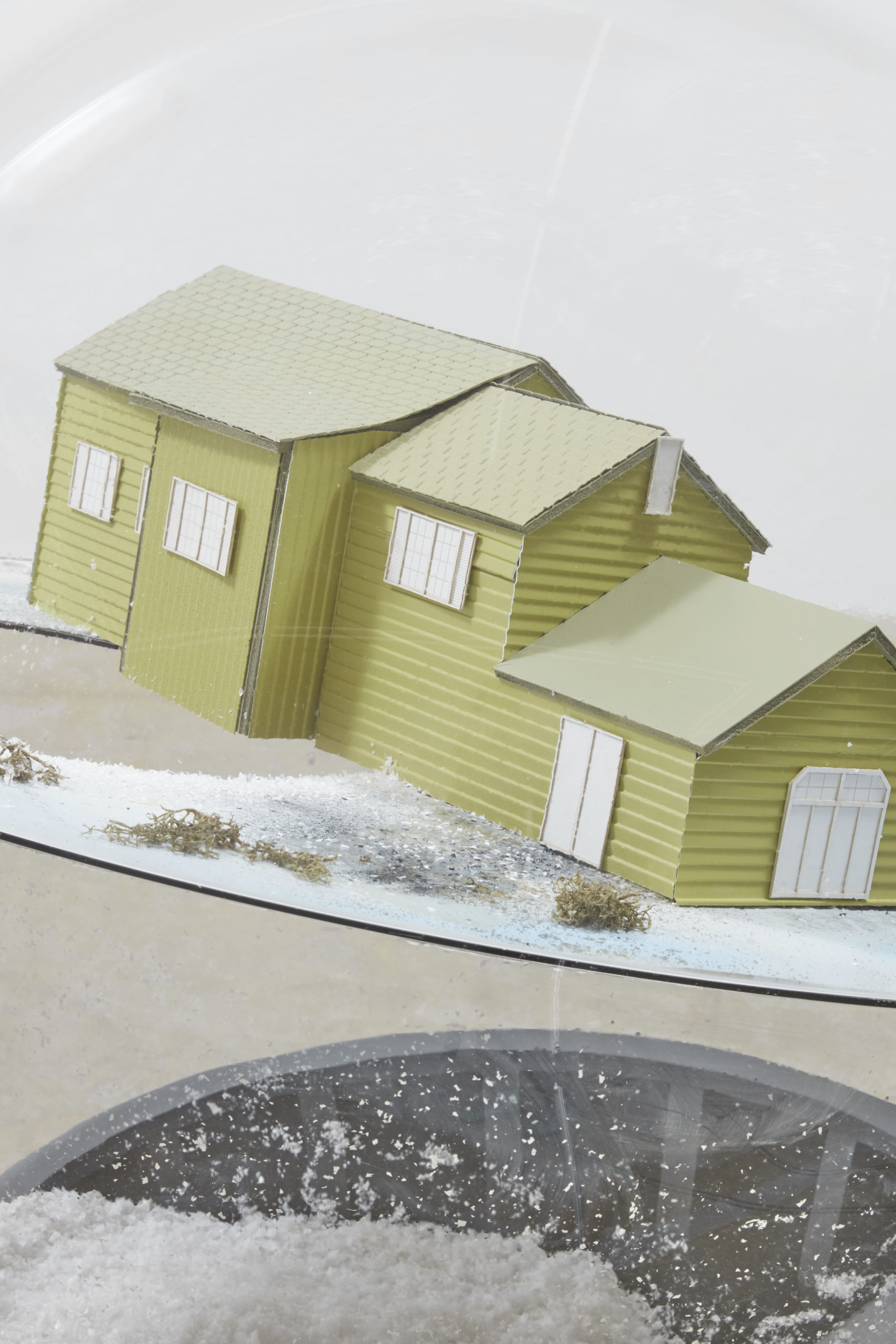

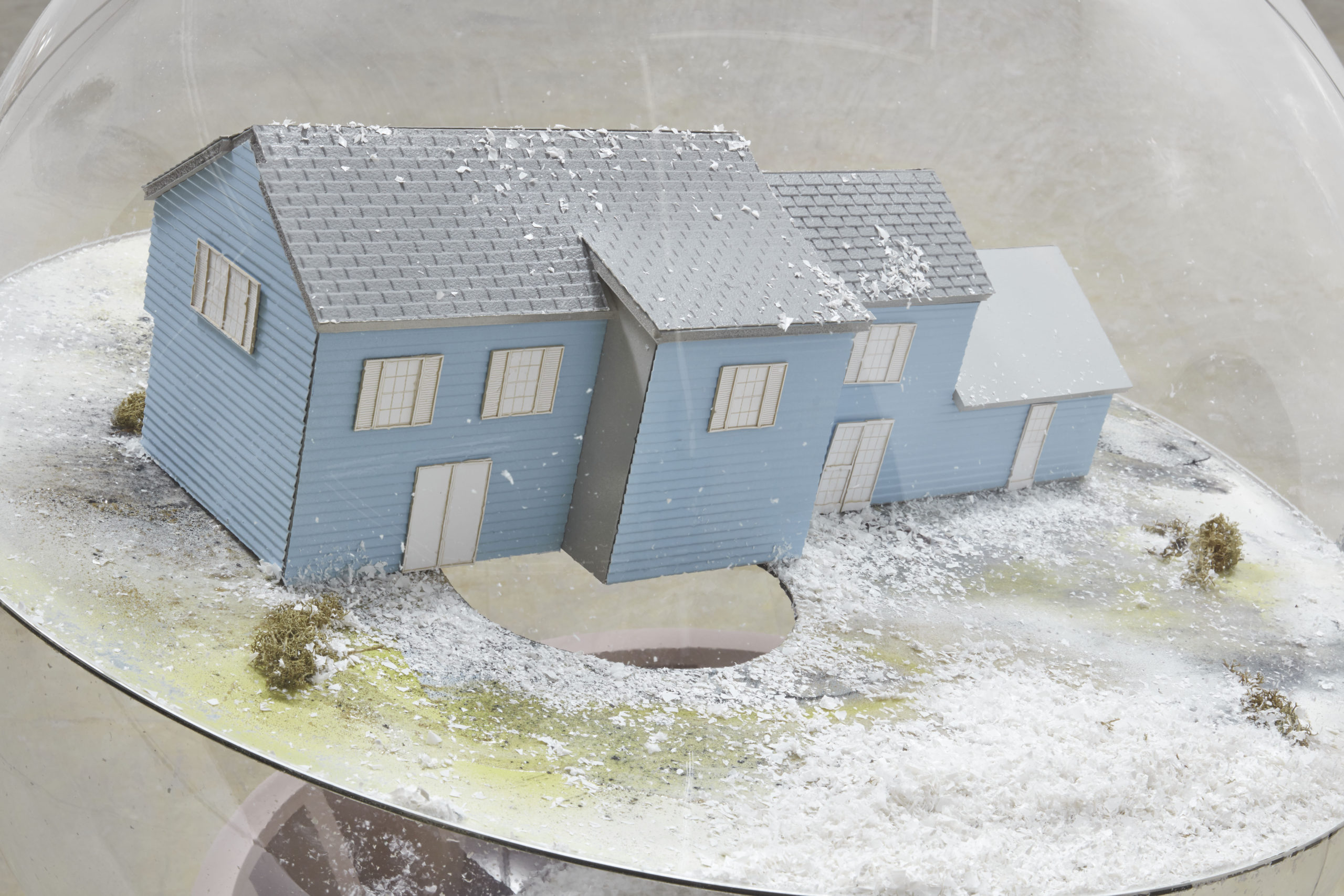

For this exhibition Erlanger takes inspiration from appearances of snow globes in cinema––citing references from Citizen Kane (1941) to Falling Down (1993)––to show the dream out-of-reach but also to create a liminal barrier between illusion and reality. In the free-standing sculptures, plexiglass spheres encapsulate three-dimensional models of typical suburban houses surrounded by muddy lawns. Erlanger deftly uses the snow globe form to magnify the contradictions of the elusive American dream: While the model houses in plexiglass cases adopt strategies of commercial display designed to generate desire, the buildings themselves are deliberately drab. The homes both construct and are victim to their environments. Flurries of artificial snow appear to swirl upward and “melt” under an equally artificial light. The tempestuous man-made weather within this internal system becomes a metaphor for entrapment and the desire to escape illusion.

The protective bubbles also provoke questions on how the individual relates to a community. Installed in the gallery, a neighborhood of homes within their own contained spheres recalls the unexpectedly isolating “filter bubble” effect of the Internet age, which encourages individuals to surround themselves with like-minded perspectives and discourages engagement with differing viewpoints. Erlanger’s sculptures offer several reminders of what’s outside our range of vision. While the globe-like works present views onto worlds, the interiors of the model homes are not visible. Rather than bisecting the homes like dollhouses and inviting voyeuristic habitation of these spaces, Erlanger keeps us at a distance, instead drawing attention to the invisible barriers that are enmeshed in capitalism.

Studies on memory show that our recall is most detailed when we can connect events and emotions to a unique place, such as a childhood home. With these scaled-down models, Olivia Erlanger plays with our temporal sense: When we see a 1950s split-level we might think we are remembering snapshots of a happy childhood; in fact, we are merely invoking a culturally-conditioned response to a life that was never ours, and never will be. However, philosopher Gaston Bachelard suggests that the idea of home is not necessarily tethered to a physical house: “The old saying ‘We bring our lares with us’ has many variations.” The sculptures may function as devices to elicit a certain set of remembrances mixed with mythos. With Split-level Paradise, Erlanger presents strategies to reckon with past visions of future worlds and makes room to conjure something different.

Olivia Erlanger (b. 1990, New York, NY) lives and works in Los Angeles. Solo exhibitions include Soft Opening, London (forthcoming in 2020); Ida, Motherculture, Los Angeles (2018); Poison Remedy Scapegoat (with Nikima Jagudajev), Human Resources, Los Angeles (2018); mouths filled with pollen, And Now, Dallas (2018); Dripping Tap, Matthew, New York (2016); The Oily Actor, What Pipeline, Detroit (2016); Dog Beneath the Skin, Balice Hertling, New York (2015). Erlanger has presented work in group exhibitions at the Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas (forthcoming in 2020); Kunsthalle Charlottenborg (forthcoming in 2020); Galleria Zero, Milan (2019); Ly Gallery, Los Angeles (2019); Capital Gallery, San Francisco (2019); M + B, Los Angeles (2018); Jonathan Ellis King, Dublin (2017); CANADA, New York (2017); Pilar Corrias, London (2015); Centre for Style, New York (2015); and Museo di Capodimonte, Naples (2014). Olivia Erlanger and Luis Ortega Govela co-wrote Garage (MIT Press, 2018), a secret history of the attached garage as a space of creativity, from its invention by Frank Lloyd Wright to its use by start-ups and garage bands.

opening January 25, 2020, 7 – 10 PM

Mr. Held’s Class, 2020

Plexiglass, architectural model, urethane resin, dibond, lichen, charcoal, wood, acrylic paint, artificial snow #15

45 x 30 x 30 in (114.3 x 76.2 x 76.2 cm)

Soft Kiss, 2020

plexiglass, architectural model, urethane resin, dibond, lichen, charcoal, wood, acrylic paint, artificial snow #15

45 x 30 x 30 in (114.3 x 76.2 x 76.2 cm)

Roseville, 2020

plexiglass, architectural model, urethane resin, dibond, lichen, charcoal, wood, acrylic paint, artificial snow #15

45 x 30 x 30 in (114.3 x 76.2 x 76.2 cm)