Bel Ami is pleased to present Bloom, a group show curated in collaboration with Orion Martin.

Four murals act as the backdrop for the show: appropriations of paintings by Michel Majerus, realized through documentation gleaned online and in books, painted directly onto the walls of the space, approximate monumental paintings never seen in person by Martin or Bel Ami. A giant sneaker next to a generically geometric abstract shape tries to replicate a 1997 installation from a group exhibition Majerus participated in at Städtische Galerie Nordhorn.

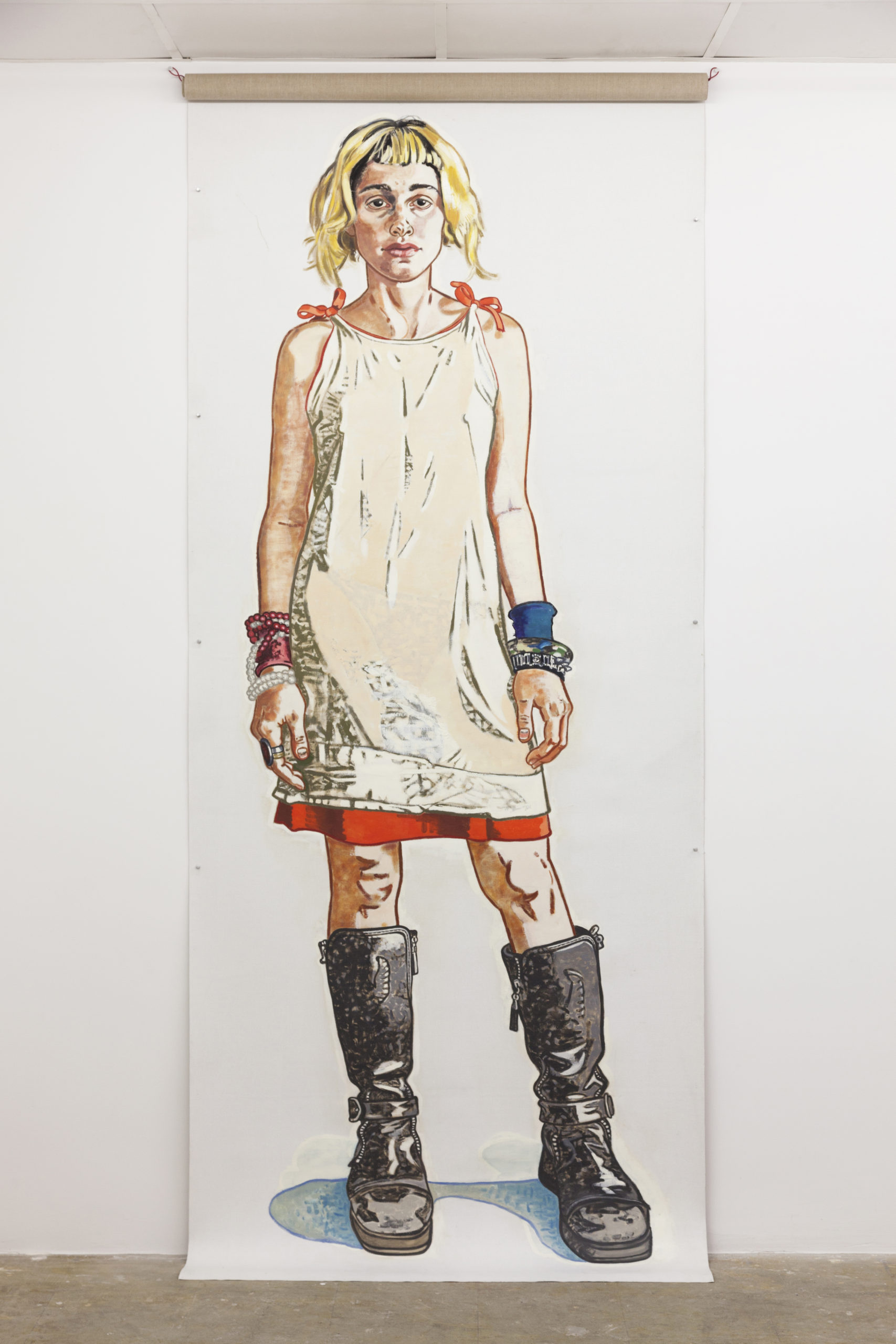

Opposite from it, Caitlin Mitchell-Dayton’s Bloom, after which the show is named, stands as an equally colossal figure: the portrait of a San Francisco art student circa 2003 rendered in beefy brushstrokes, it encapsulates the era’s perfectly indie style. Feeling as fresh now as fifteen years ago, and transcending its documentarian impulse, the burgeonning identity of the young larger-than-life woman appears almost like an icon, similar to Watteau’s Pierrot, which once possibly hung as a sign in a café (it now hangs in the Louvre). Can the same shoe be attractive to everyone, and forever?

Nearby, Flannery Silva’s Bumper Ballerina sits. Based on a bird cage-like prison with a heart dangling inside, featured in the world of Elisa Design—an online illustrator who Silva purchases digital doll renderings from—Silva’s version is covered in foam tubing that acts as a protective bumper, similar to what you’d see on the bars of a baby’s crib or the handlebars of a child’s bicycle. Hanging inside the cage are two dangling novelty fishing lures shaped like penises. They are positioned to echo a ballerina’s legs en pointe, dangling above a reflective dance floor, mirroring the cage, its content and its surroundings in a circular pool of hot pink.

Sean Kennedy’s paintings on plexiglas circles originate from the designs of NASCAR automobiles, which sport sponsors’ logos as well as more incongruous graphics. Kennedy’s distorted versions render the speedy advertorial as formal autonomy brought to a stand still. While Untitled (2016-2018) is based on a 1980s design promoting BASF’s brief foray into the manufacturing of audio equipment, as suggested by soundwave-like patterns, Untitled (2018) is freed from direct branding references, looking like they are about to start spinning, perhaps like tires, perhaps like Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs.

Two paper mache sculptures by Carol Jackson feature degraded surveillance images found on the Internet, the best contemporary repository of oral culture, showing scenes of wildfires. Looking like their sliced sides open up to a landscape within, they are both alien artifacts in their strangeness and unmistakably human in their sampling of decorative language and their handmade quality. In anticipation of the apocalypse—or has it happened already?—Jackson’s sculptures testify to the banality of disasters, while casting a nearly nostalgic gaze on the deadpan slapstick comedy that is the end of human civilization.

Forever lifeless and fixed in an unclear position—is she paying respect to her patients, or simply curtsying?—Miriam Laura Leonardi’s sculpture Angels of Chaos 4 depicts a nurse, spiked onto the stem of a desiccated plant. Greeting the visitor, its eyes glowing, its face carved by a Swiss carnival mask-maker. The sculptures in the ongoing Angels of Chaos series depart from works of female artists that include a flower in their margins, which Leonardi uses as starting points for her paradoxical assemblages, in which her own expression appears hushed in the same black and white auto-portrait (her gesture copying an unknown Dada artist). The straw on Angels of Chaos 4 refers to the same material sprouting from the top of Meret Oppenheim’s 1962 Primeval Venus.

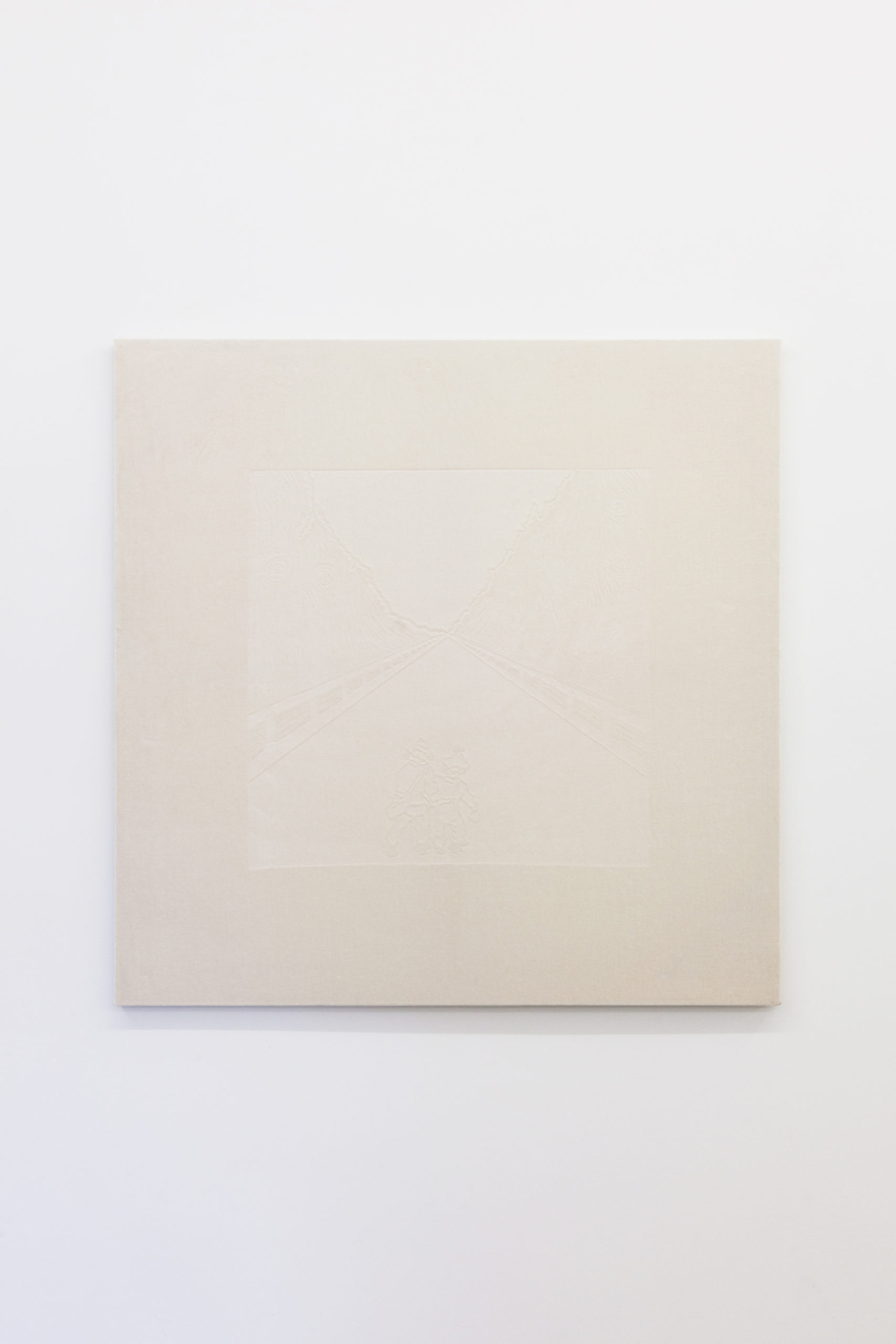

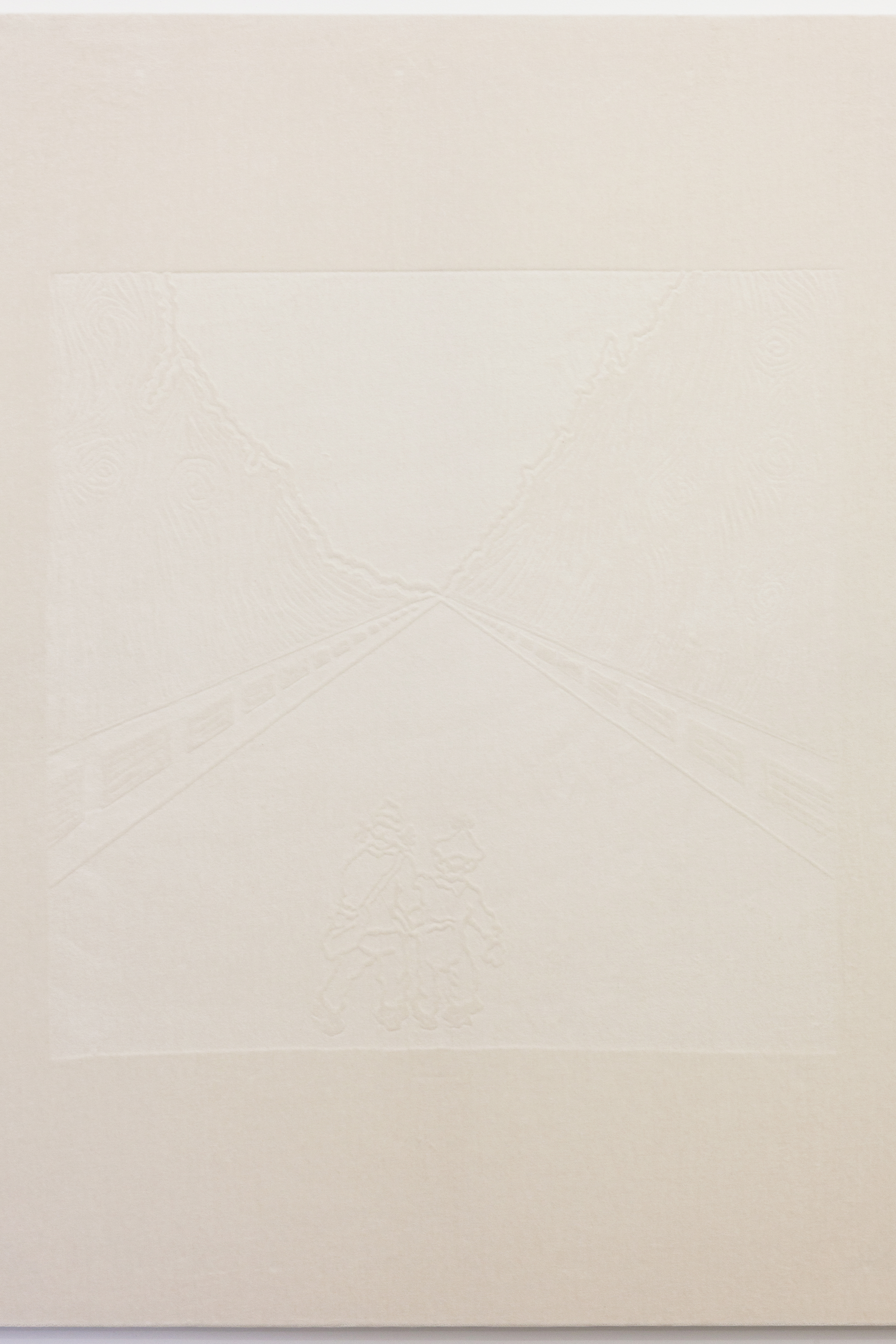

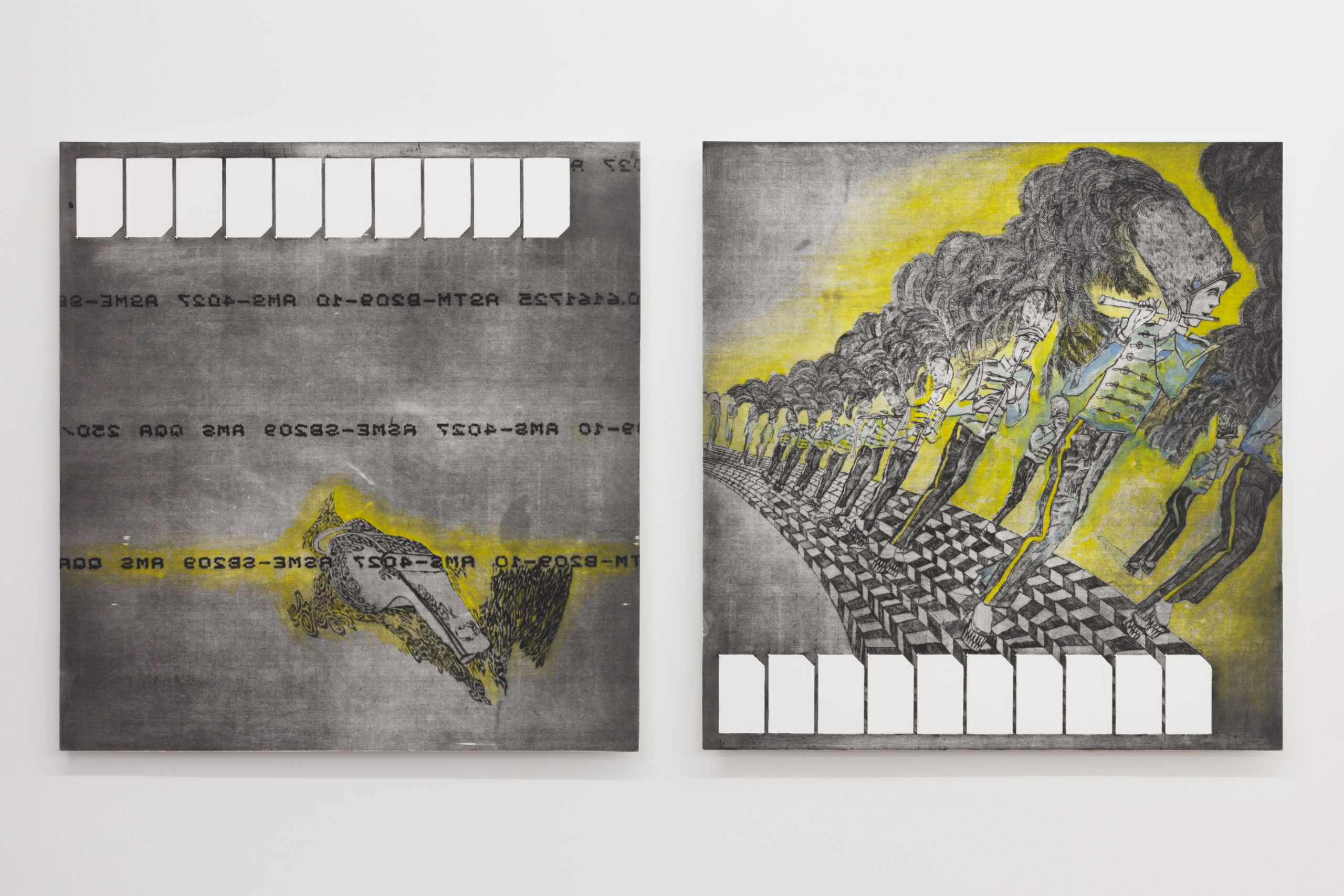

Almost-stock and found characters also make their way into Cédric Eisenring’s works. A marching band, the purpose of their parade uncertain, appears in Soft Parade, a diptych of etchings made with modified discarded industrial printing plates. Two fairy-tale-like children, originating in a shoe advertisement, but later found on the cover of Simon Finn’s 1970 psychedelic folk album Pass the Distance, faintly head toward the horizon in Still Close Friends, a white-on-white pressed velvet work. The psychedelia in Eisenring’s works, at once gentle and off-putting, draws from various narratives—children’s books to Sci-Fi literature—and is generated through elaborate processes mixing both classical and digital techniques. It is psychedelia both of our fantastic imagination and of the world now, far far away from its ubiquitous sources.

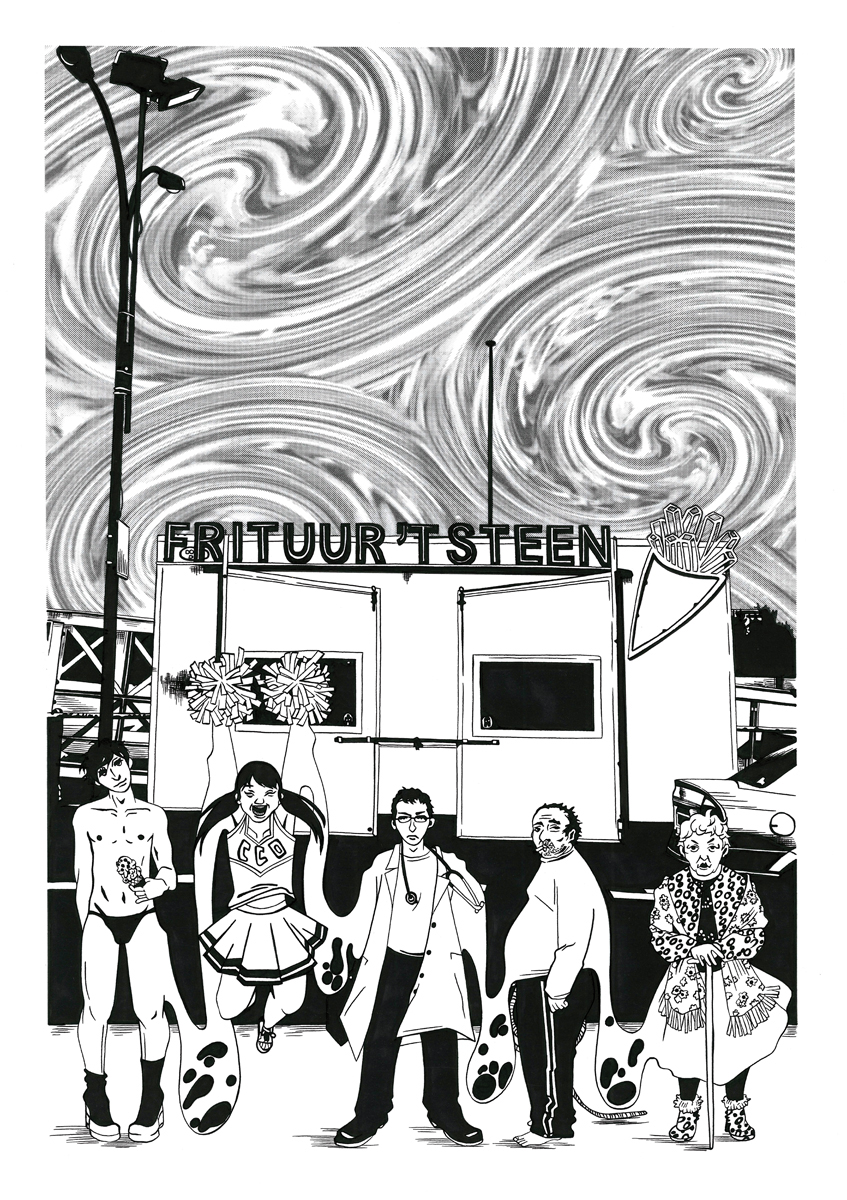

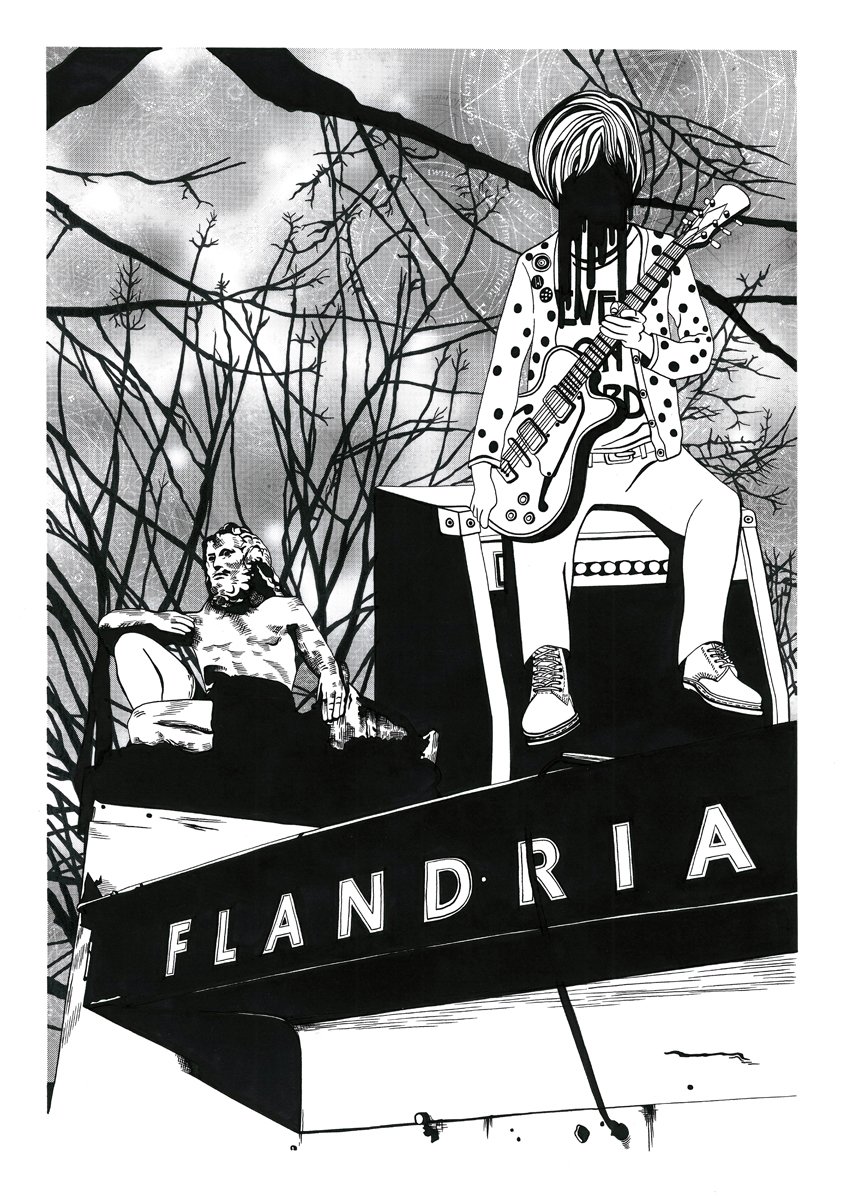

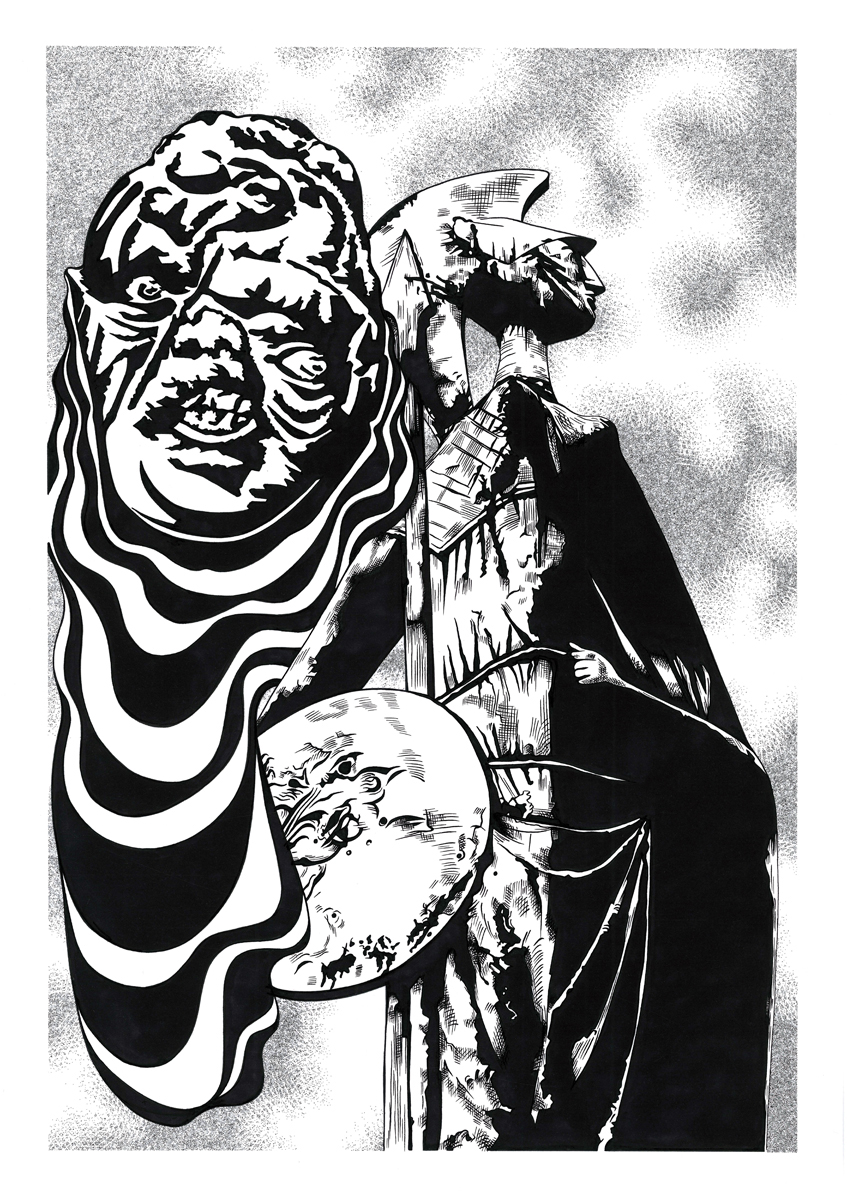

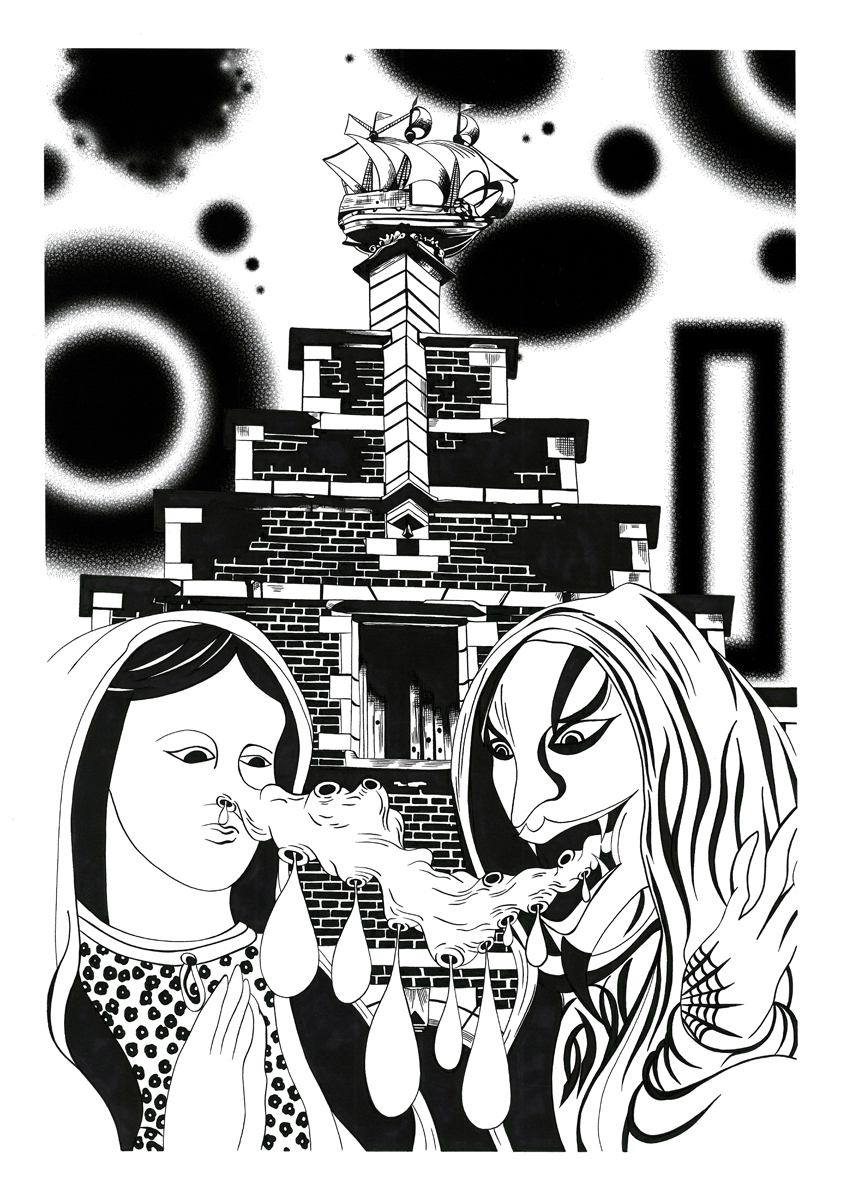

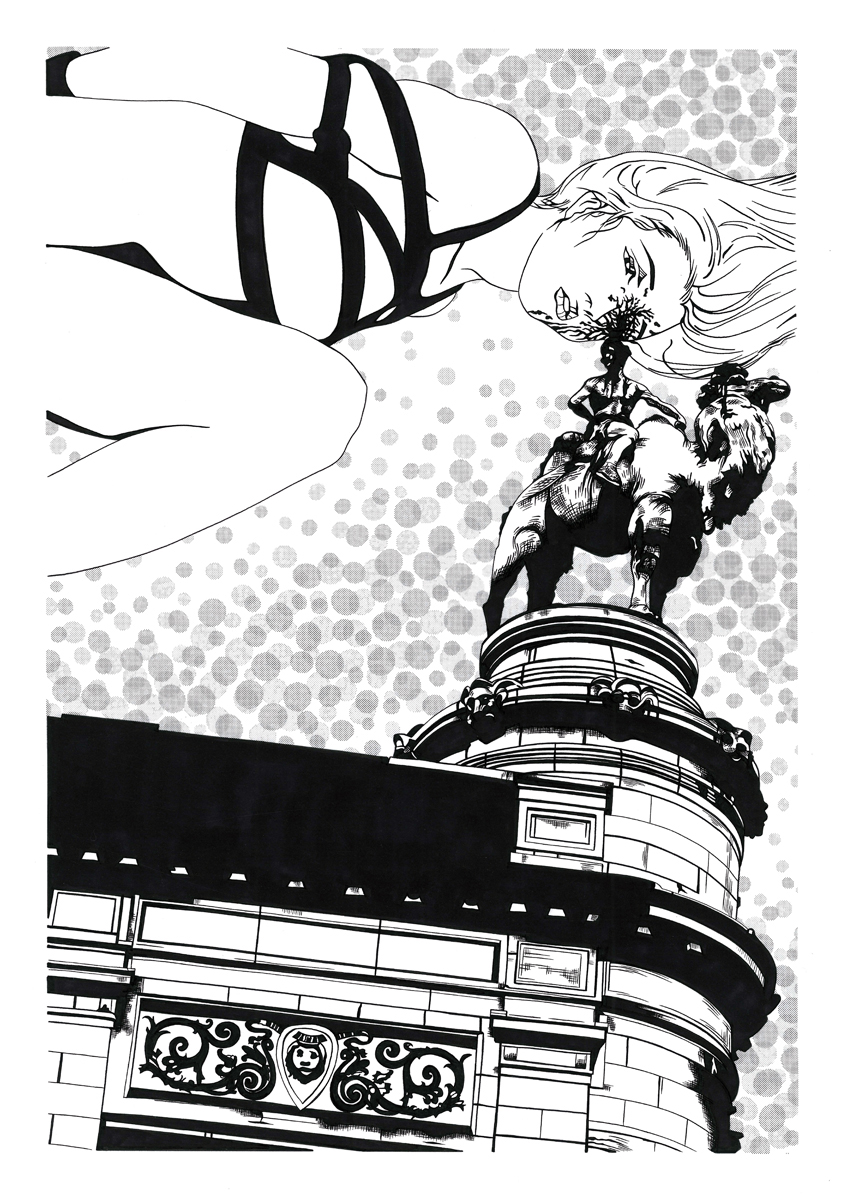

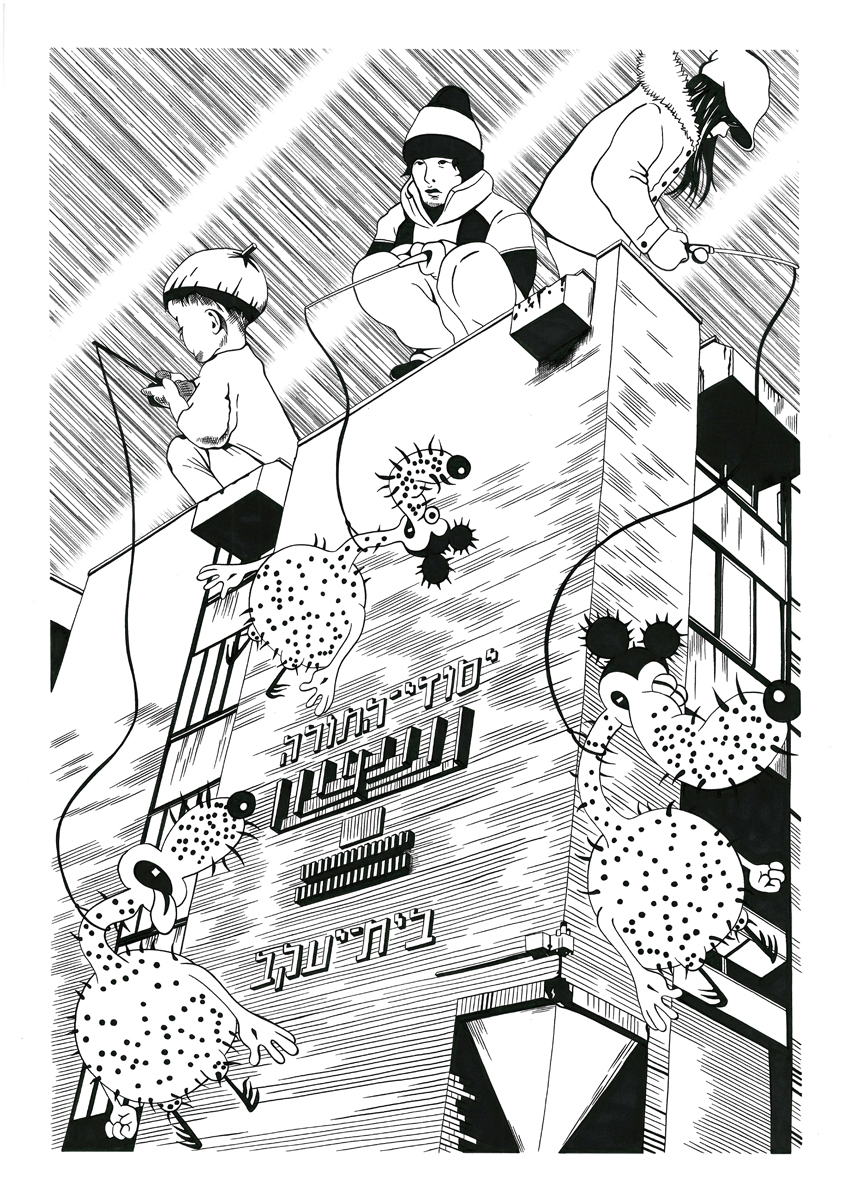

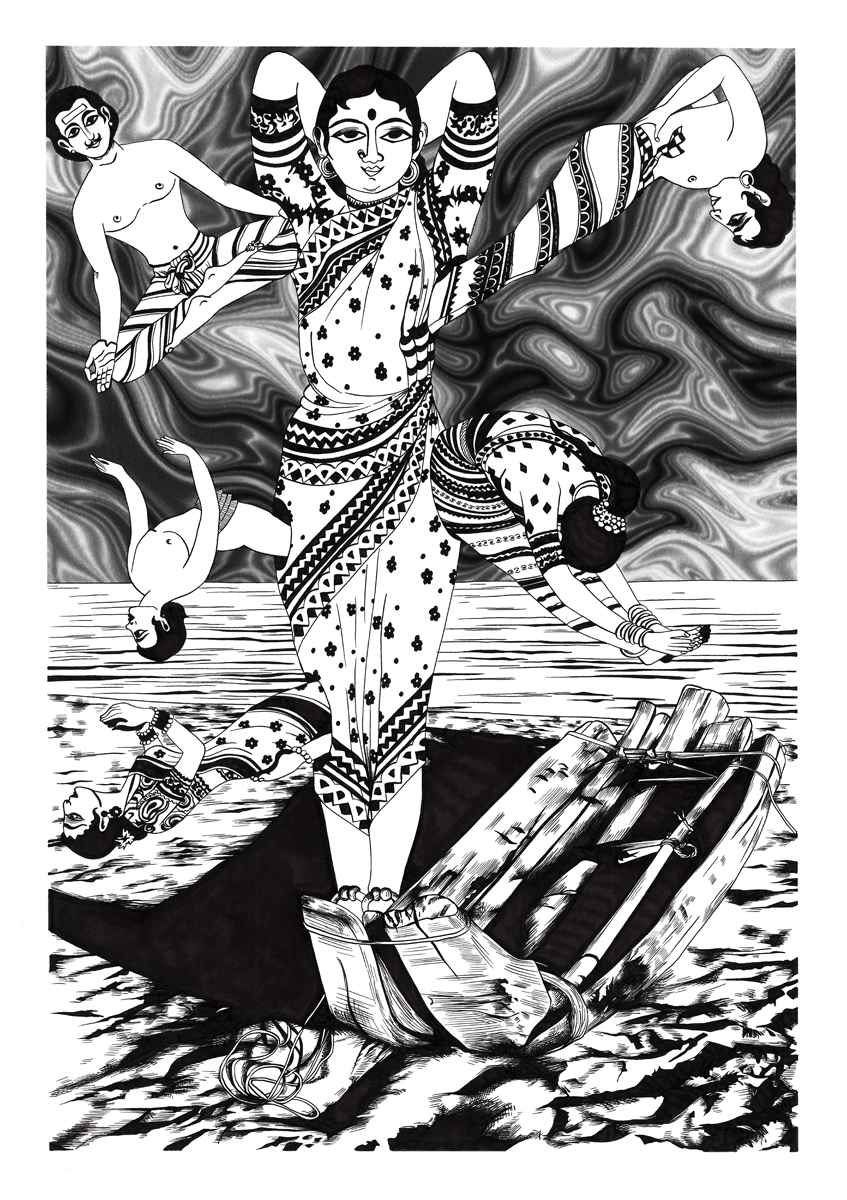

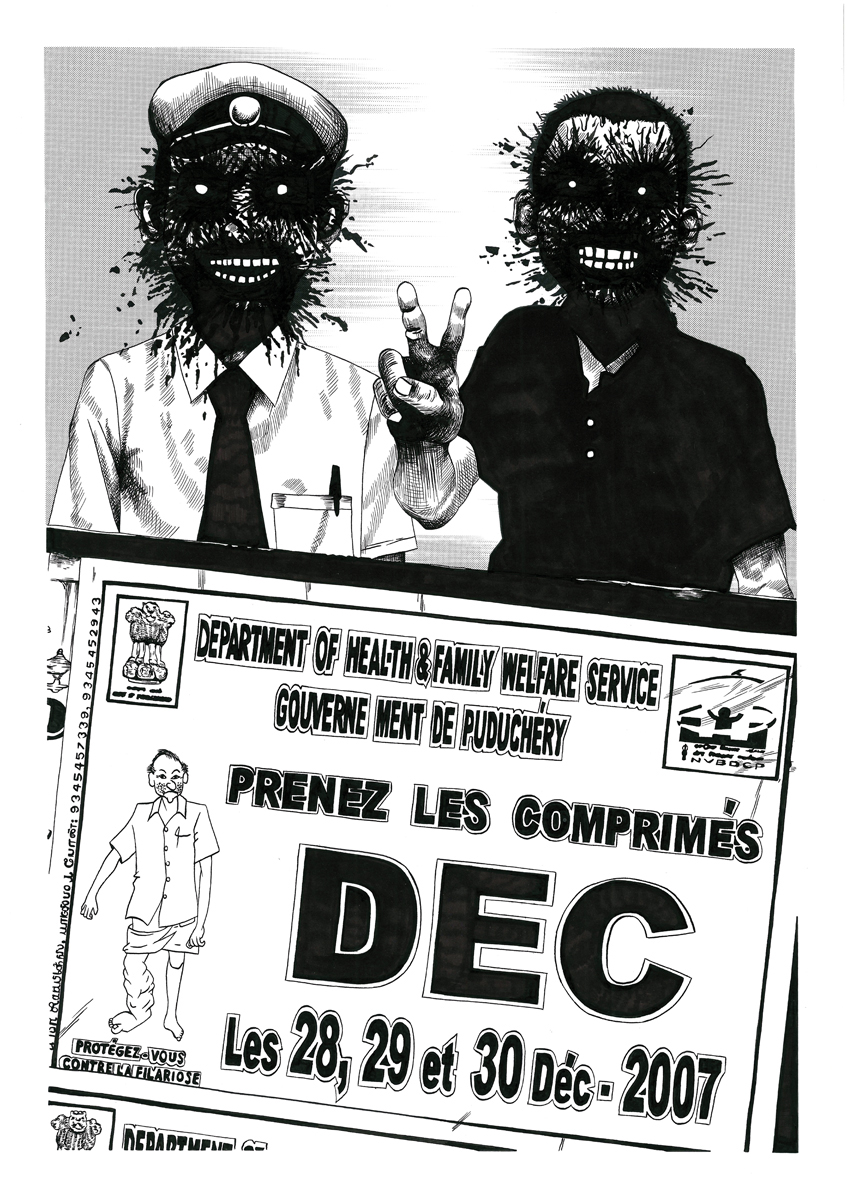

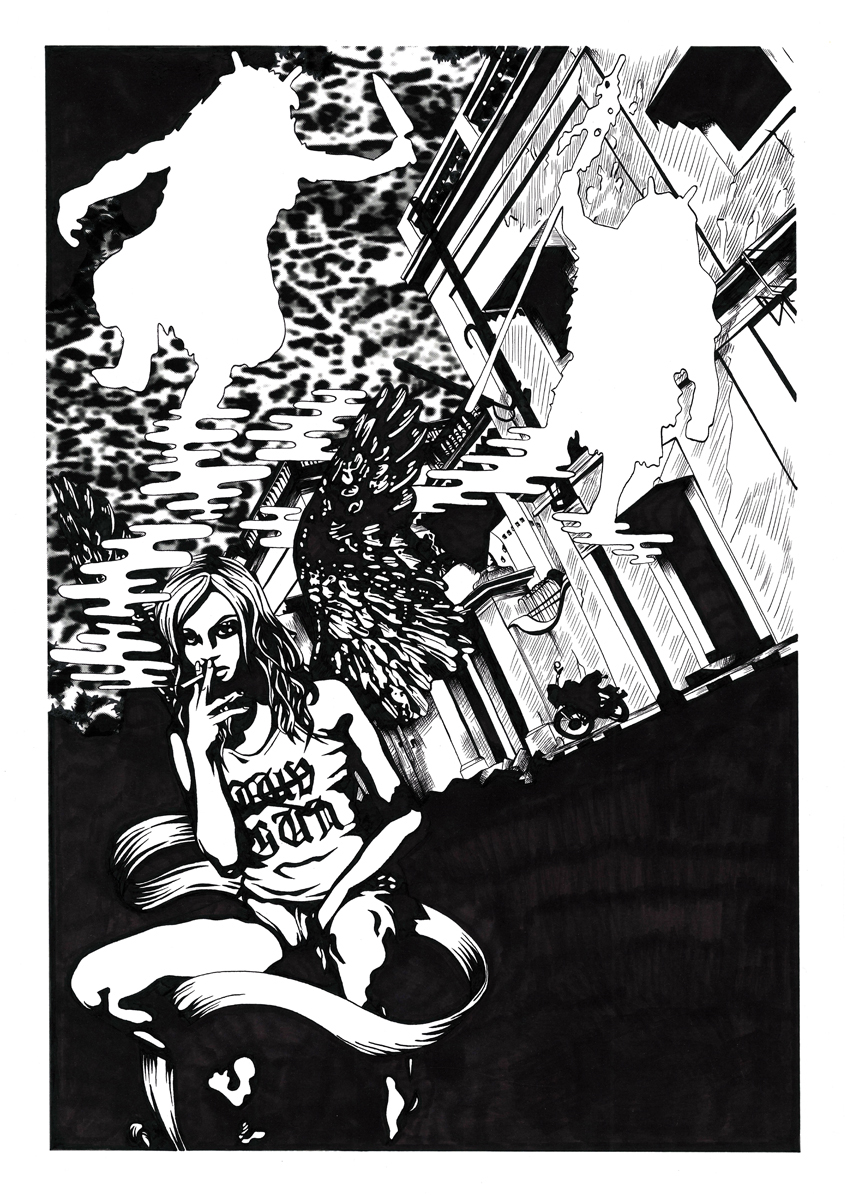

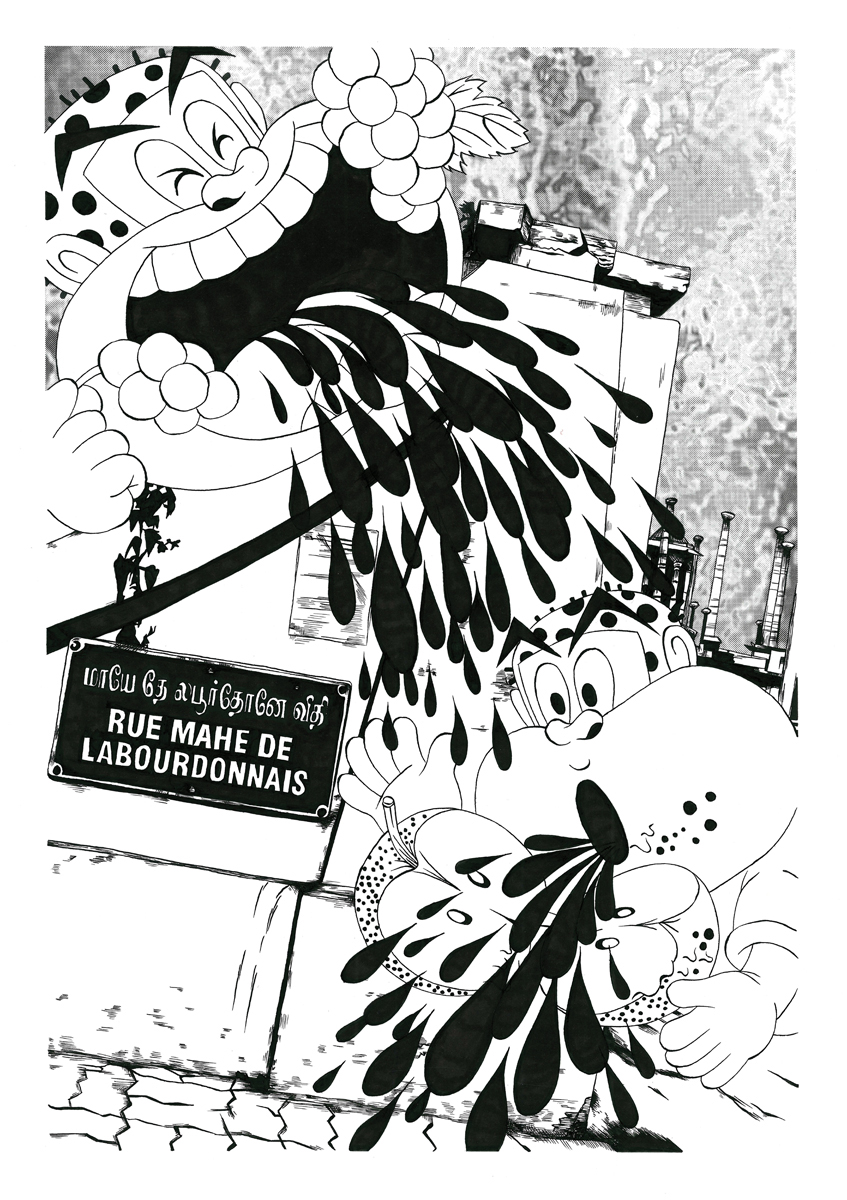

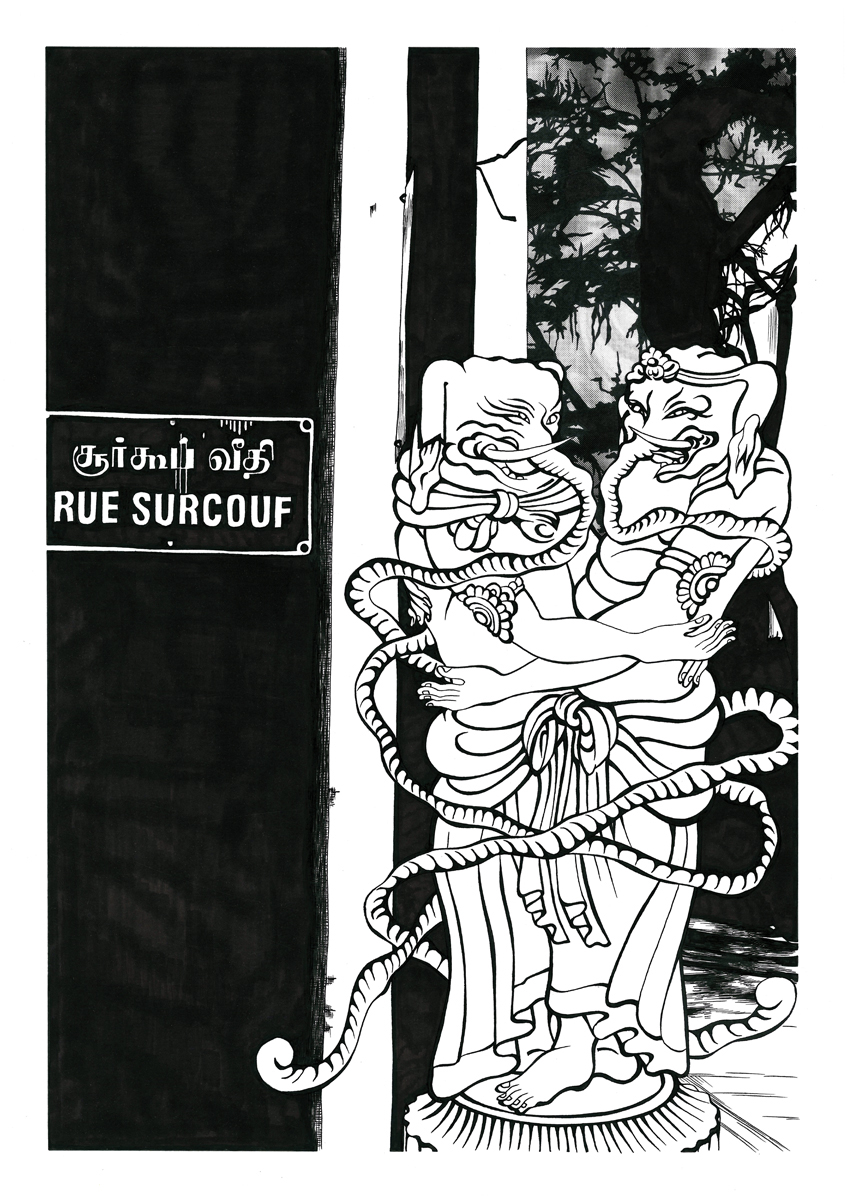

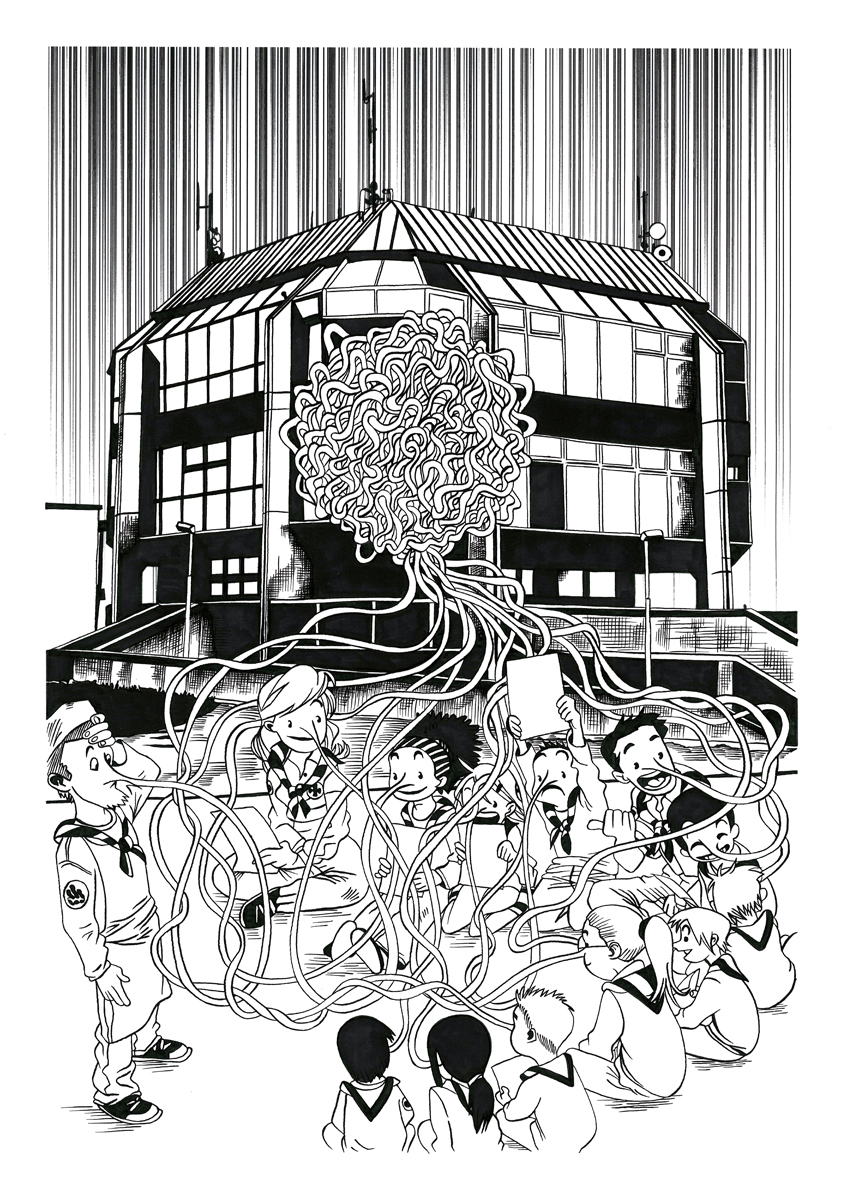

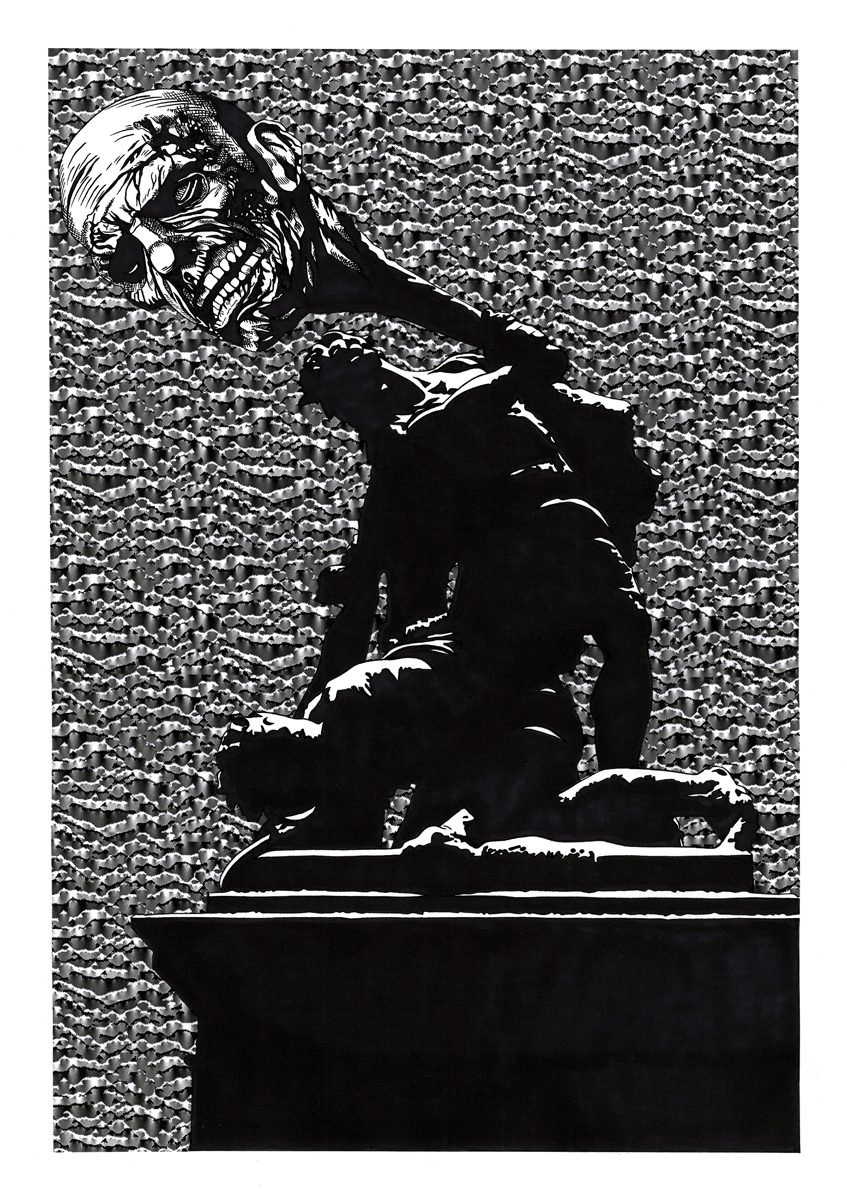

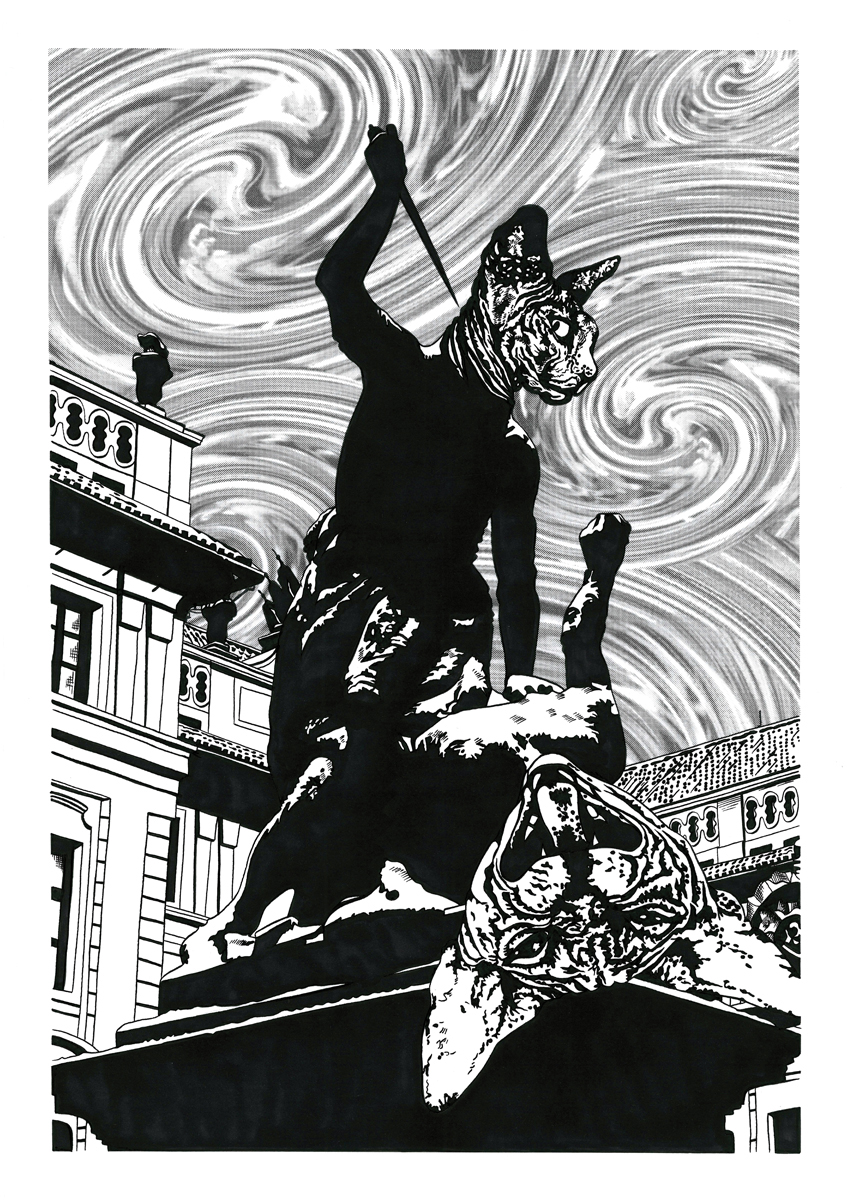

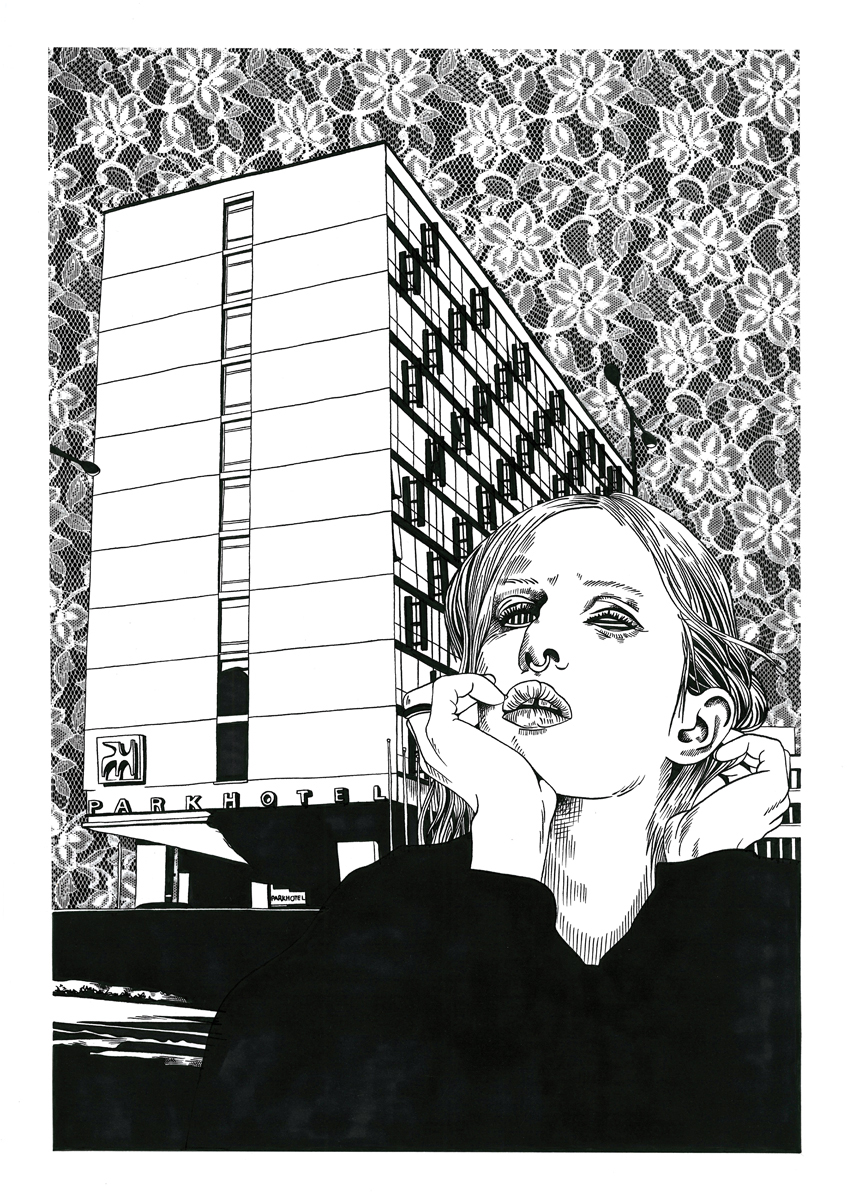

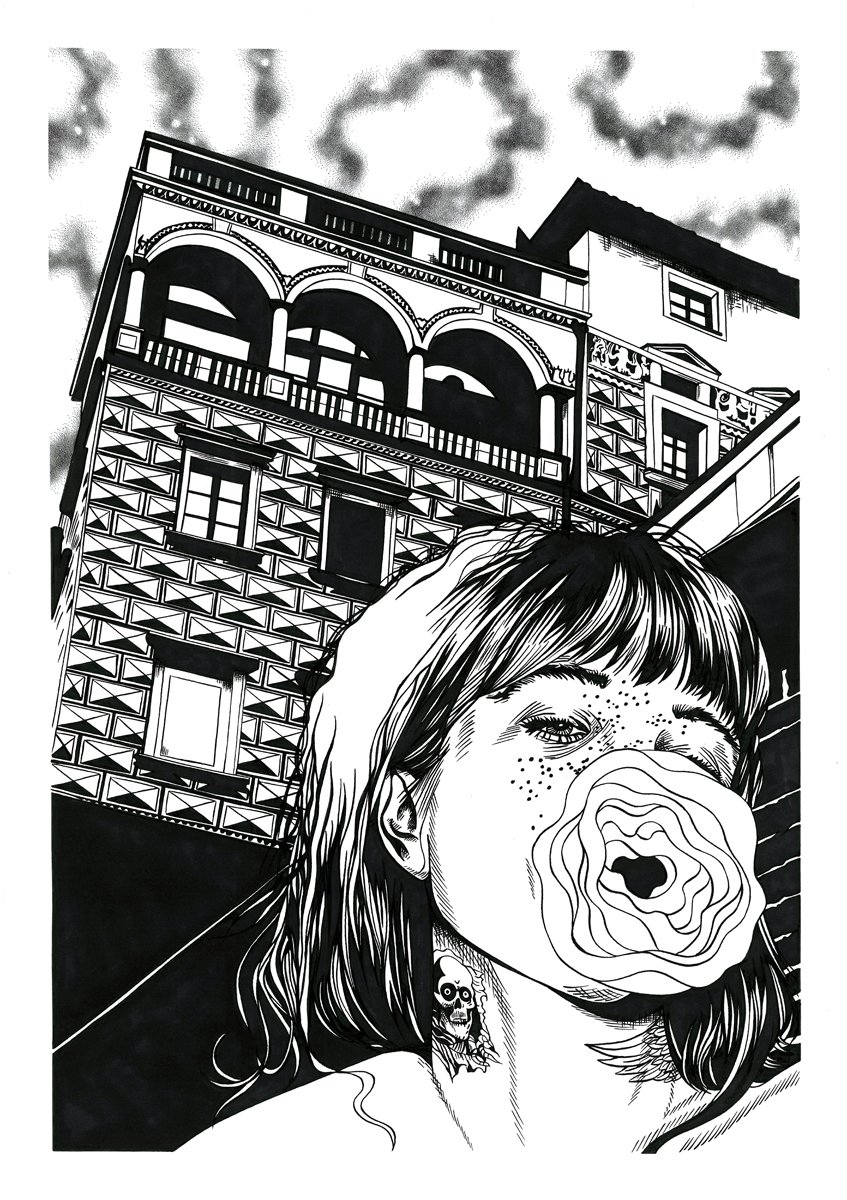

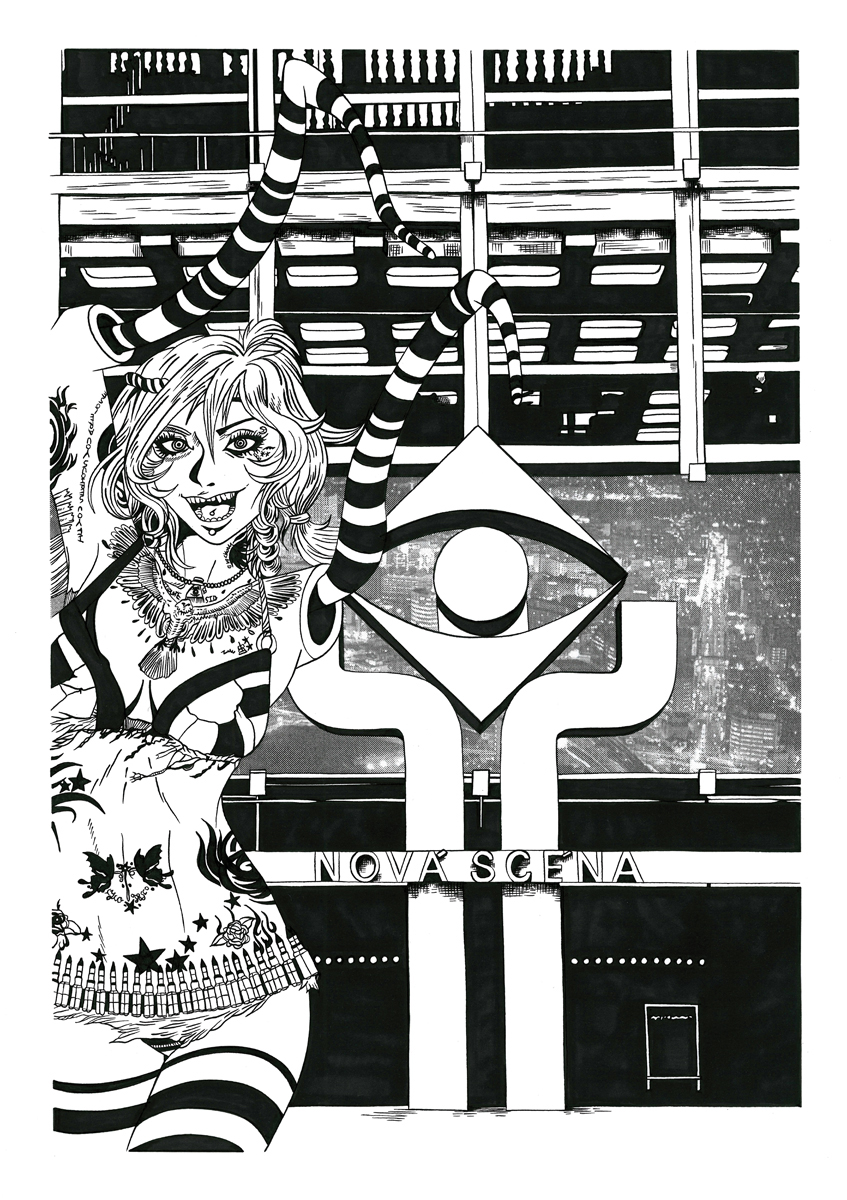

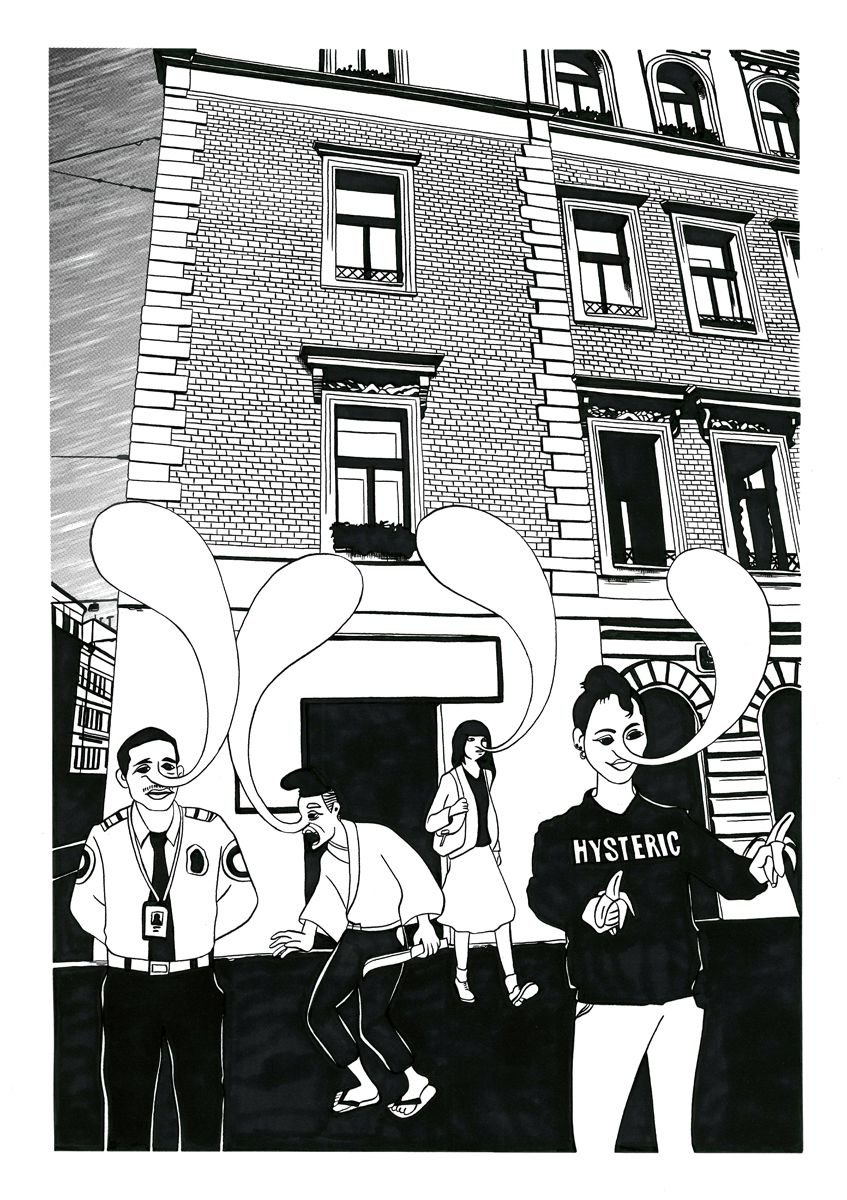

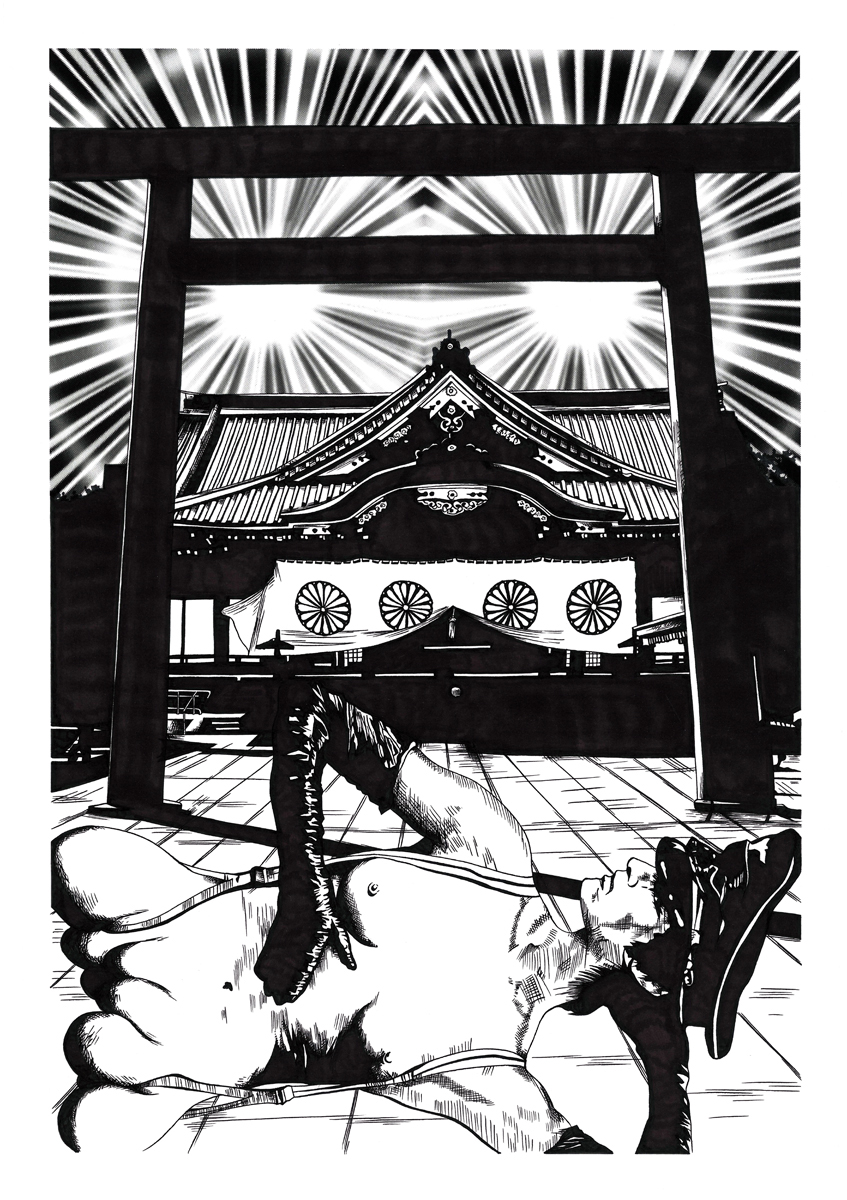

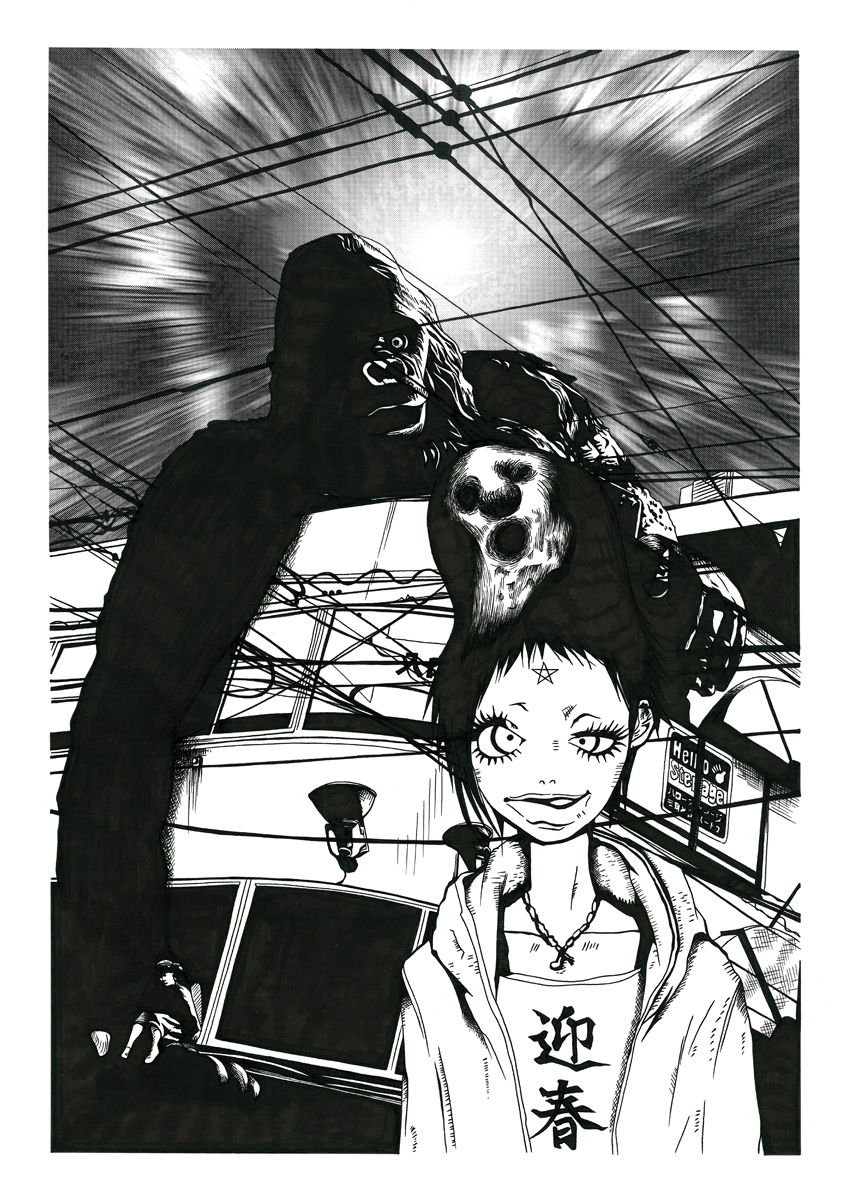

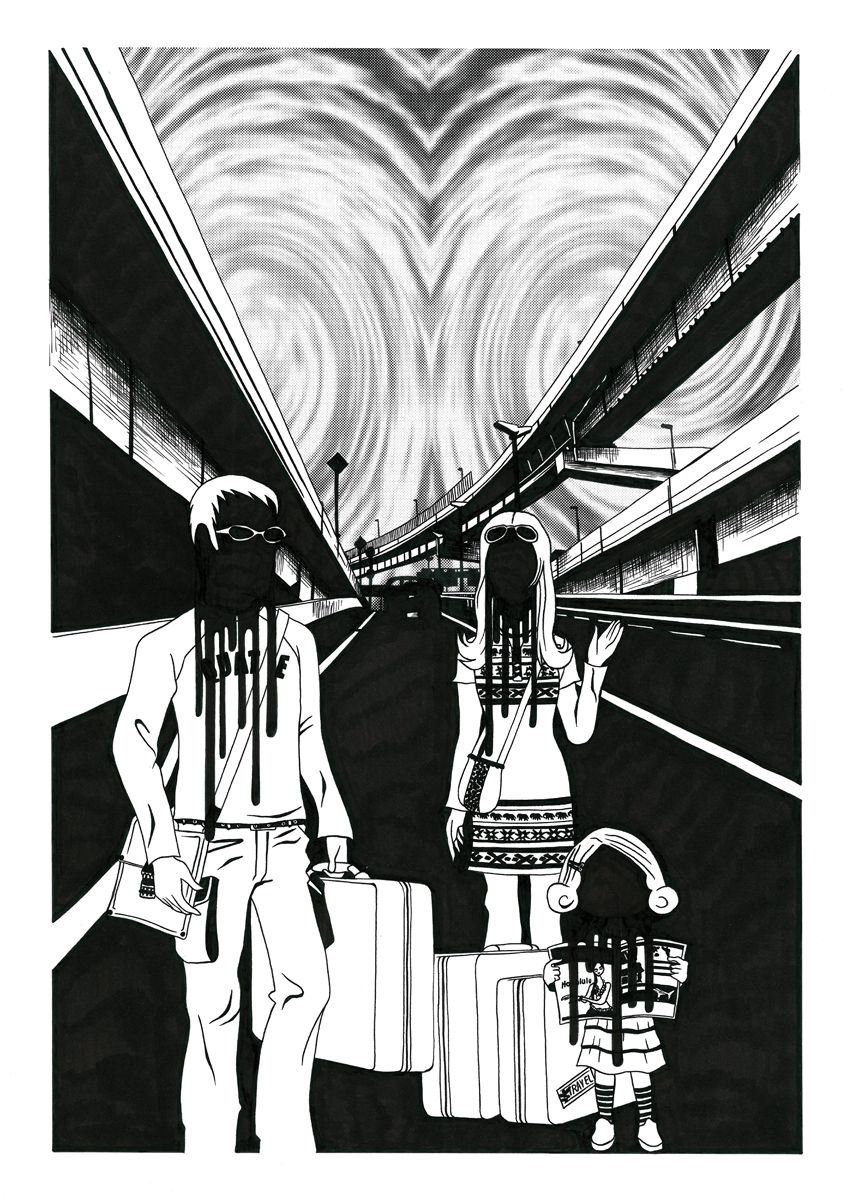

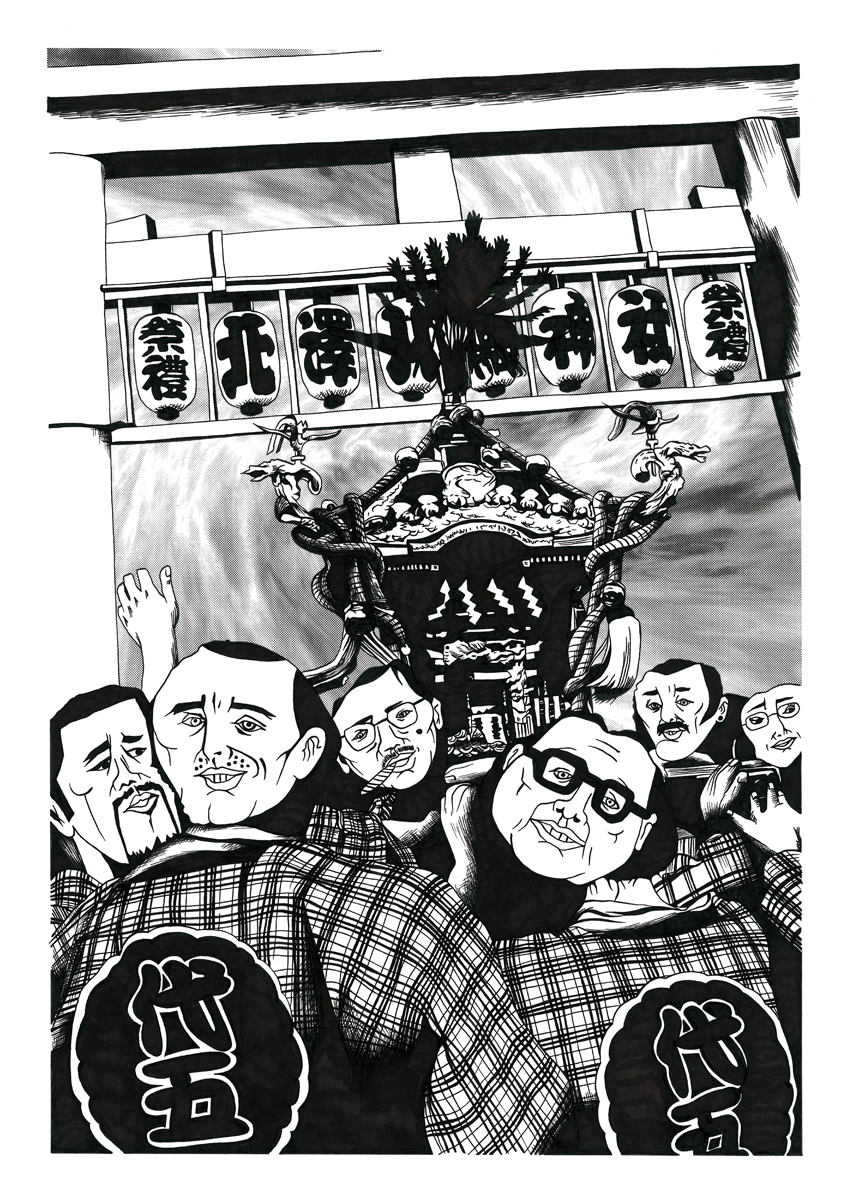

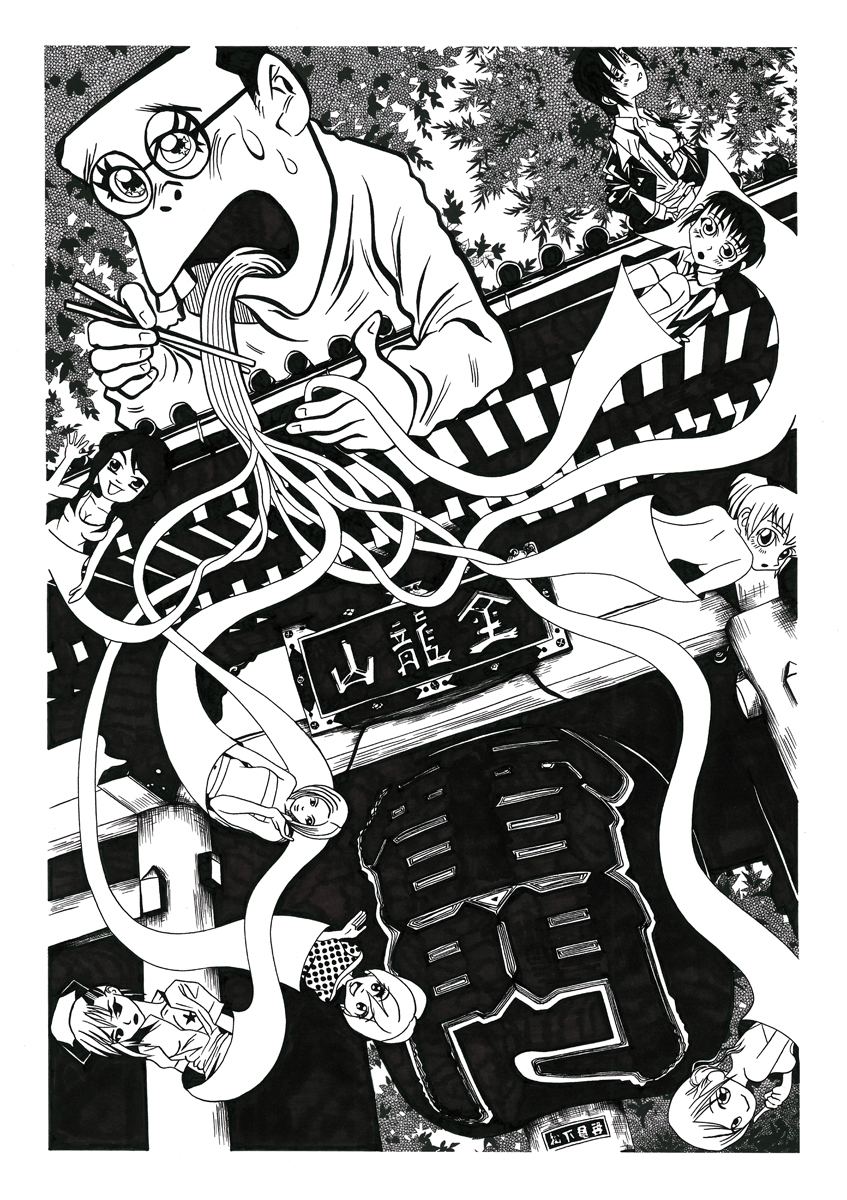

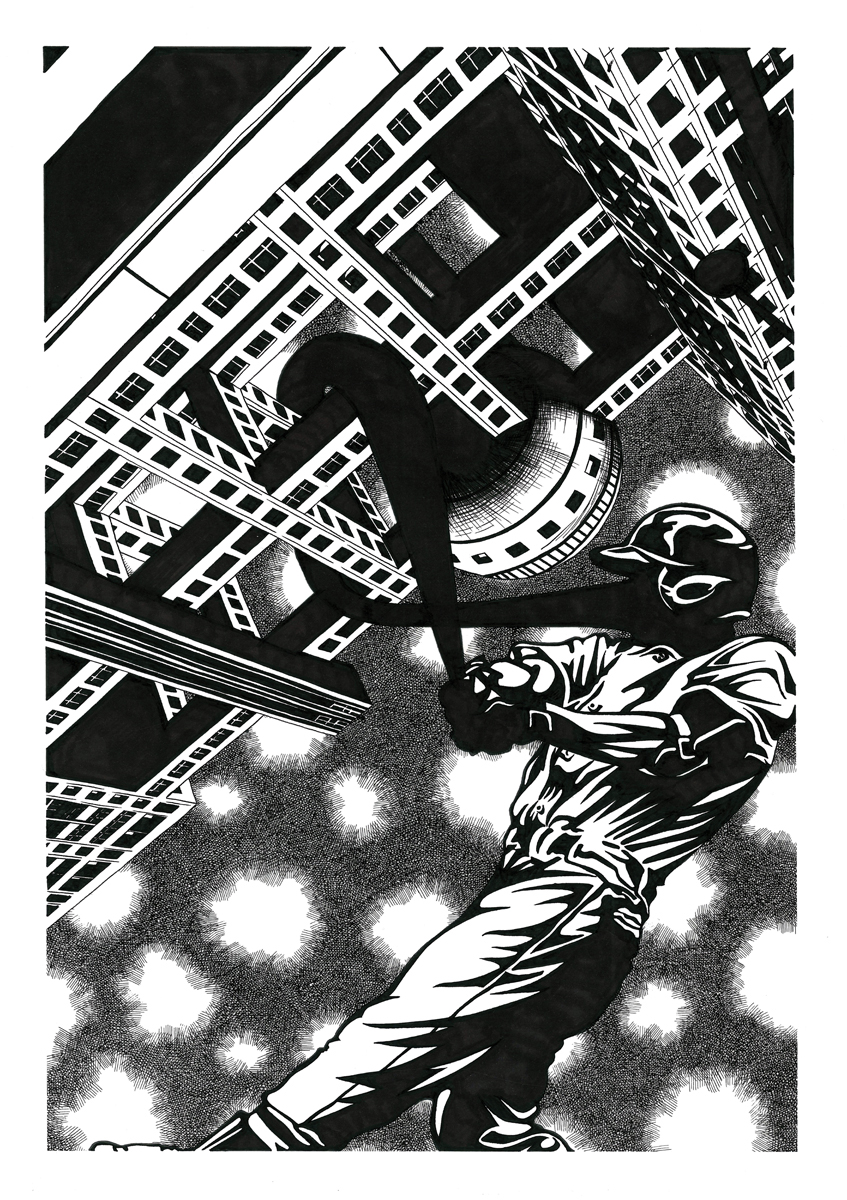

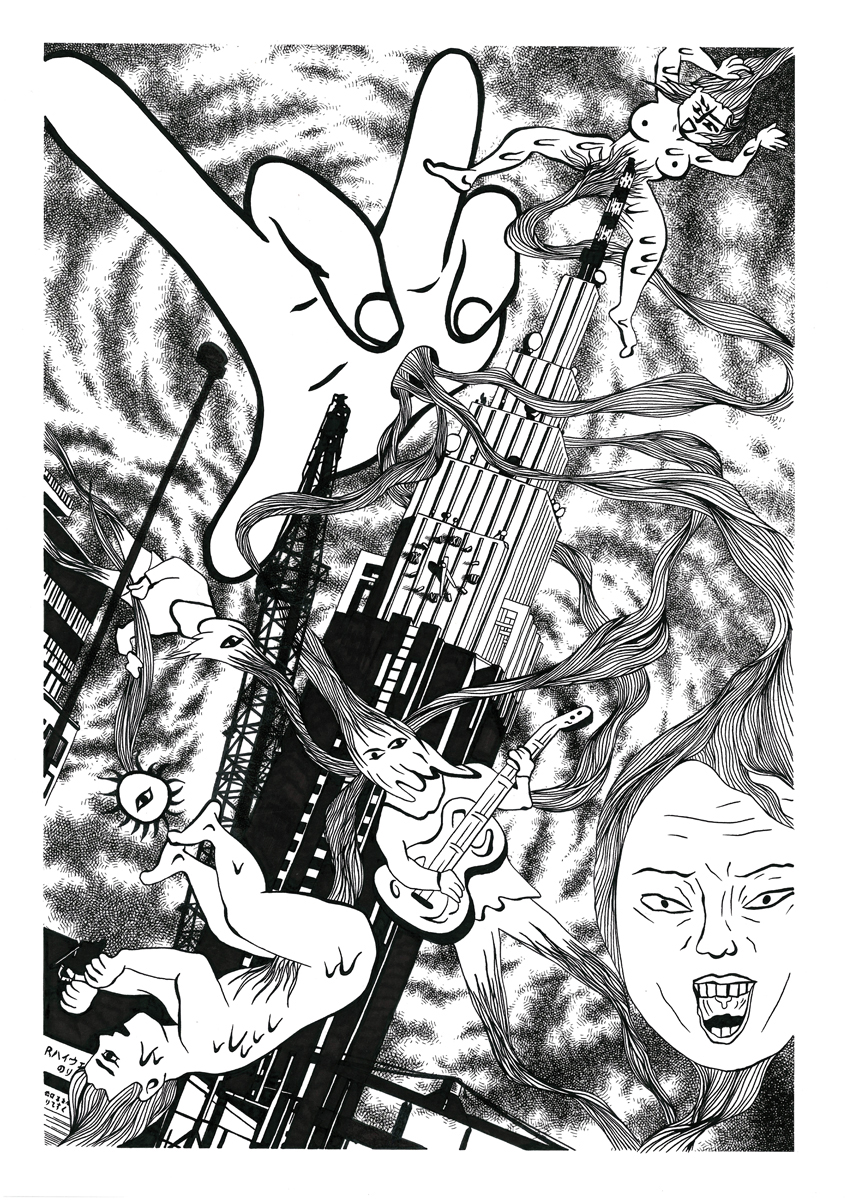

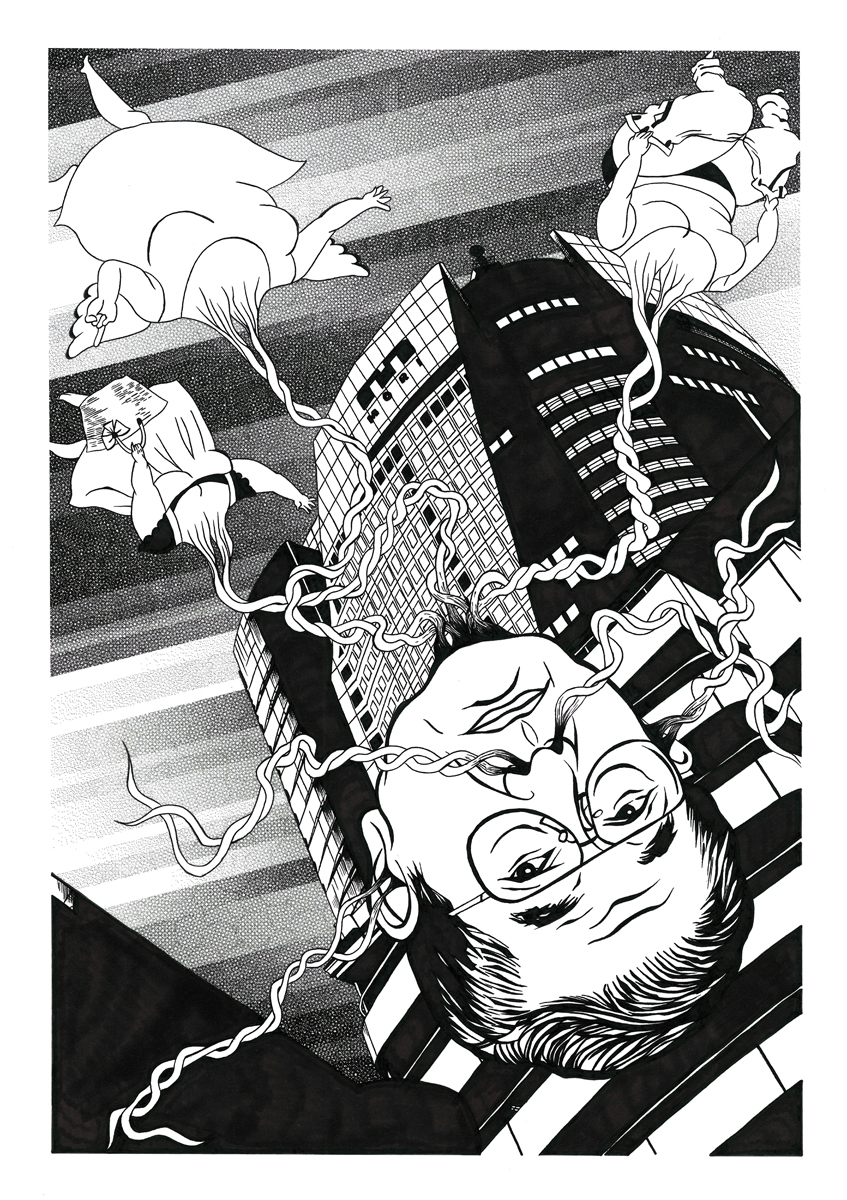

Ubiquity manifests as a riotous mix of real locations and fictional characters in Matthieu Manche’s drawings from his Sekaido series: everybody, everything, everywhere, all the time. Made using the materials and techniques of manga drawing, the black-and-white works on paper juxtapose snapshots from Manche’s travels around the world and elements from characters found in daily life in Tokyo, where Manche lives part-time. Sekaido is the prime art supply store in Tokyo and literally means “the world store.” The entirety of the series, comprised of 768 works divided in 102 subgroups, realized between 2004 and 2016, presents a world populated by the twisted, the contorted, the disfigured: at Bel Ami, a selection of four subgroups of scenes set in Antwerp, Prague, Tokyo and Pondicherry playfully toys with archetypes and tourism, patchworked signs escaping their original intentions.

Majerus died in a plane crash in 2002 at the age of thirty-five, the contents of his laptop lost in the accident.

opening September 25, 2018, 7 – 10 PM

Caitlin Mitchell-Dayton

Bloom, 2003-2004

oil on unstretched linen

134 x 46 1/2 in (340 x 118 cm)

Flannery Silva

Bumper Ballerina, 2018

MDF, metal, paint, foam, mirrored acrylic, novelty fishing lures

27 x 47 x 47 in (69 x 119 x 119 cm)

Carol Jackson

Two Doors Down, 2016

paper mache, epoxy putty, acrylic, inkjet print, enamel

25 x 25 x 23 in (63.5 x 63.5 x 58.5 cm)

Carol Jackson

drills, 2017

paper mache, acrylic, ipolymer clay, digital print

15 x 8 x 16 in (38.1 x 20.3 x 40.6 cm)

Miriam Laura Leonardi

Angels of Chaos 4, 2018

wooden mask, reading lamp, clothing (jeans, blouse, cap, socks, shoes), plastic hands, plexiglas sphere with black and white print, metal wire and bars, darning wool, straw

70 x 45 x 36 in (180 x 120 x 92 cm)

Sean Kennedy

untitled, 2016-2018

latex paint on acrylic, machine screws, aluminum standoffs

45 x 45 x 1 in (114.3 x 114.3 x 2.5 cm)

Sean Kennedy

untitled, 2018

latex paint on acrylic, machine screws, aluminum standoffs

33 x 33 x 1 in (83.8 x 83.8 x 2.5 cm)

Cédric Eisenring

Still Close Friends, 2018

woodcut intaglio print on velvet

40 1/2 x 40 1/2 in (103 x 103 cm)

Cédric Eisenring

Soft Parade, 2018

dry point etching with used industrial plates and watercolor on paper

diptych, each 27 3/8 x 26 1/8 in (69.6 x 66.3 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Antwerpen 01), 2013

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Antwerpen 02), 2013

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Antwerpen 03), 2013

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Antwerpen 06), 2013

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Antwerpen 07), 2013

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Antwerpen 09), 2013

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Pondicherry 02), 2009

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Pondicherry 07), 2009

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Pondicherry 08), 2009

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Pondicherry 09), 2009

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Pondicherry 11), 2009

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Praha 02), 2015

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Praha 04), 2015

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Praha 06), 2015

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Praha 08), 2015

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Praha 09), 2015

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Praha 11), 2015

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Praha 13), 2015

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Tokyo 07), 2010

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Tokyo 13), 2010

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Tokyo 15), 2010

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Tokyo 19), 2010

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Tokyo 20), 2010

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Tokyo 22), 2010

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Tokyo 24), 2010

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Matthieu Manche

Sekaido (Tokyo 25), 2010

ink and screentone on paper

14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in (36.3 x 25.7 cm)

Orion Martin

Peppermill Orion, 2018

oil on canvas

20 x 15 in (51 x 38 cm)