“They talked, as human beings do, about what they didn’t know.”[1]

In Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Shobies’ Story, which inspires Rosalind Nashashibi’s most recent film, a crew of ten volunteers from four different cultures board a ship to test a new faster-than-light form of space travel. As the Shoby leaps through time and space, communication disintegrates. The perceptions of the crew vary wildly, destroying their capacity to operate the ship, or even look out for one another’s safety. In a desperate reenactment of ancient tradition, the Shobies gather around an artificial fire to collectively recount their experience, leaving out or resolving contradictions until the narratives cohere. They are then able to return home and report their agreed-upon account to a team of scientists. Le Guin’s story suggests that telling tales, though chancy and unreliable, is still the most effective means of constructing a shared reality.

This exhibition explores both the impulse to tell stories, and the risk. Narratives, inscribed with unspoken desires and hidden fears, often reduce reality’s complexity for the sake of coherence, setting off reverberations which all too frequently result in racial, ethnic, gender, or class misreadings. As semiotician and film scholar Teresa de Lauretis once wrote, “much is at stake in narrative, in a poetics of narrative. Our suspicion is more than justified, but so is our attraction.”[2] In this exhibition, four artists, Rosalind Nashashibi, Diane Severin Nguyen, D’Ette Nogle, and Miljohn Ruperto, open up our capacity to read objects, images, gestures and situations, while raising our awareness of the danger of the very human tendency to compel them into linear narratives.

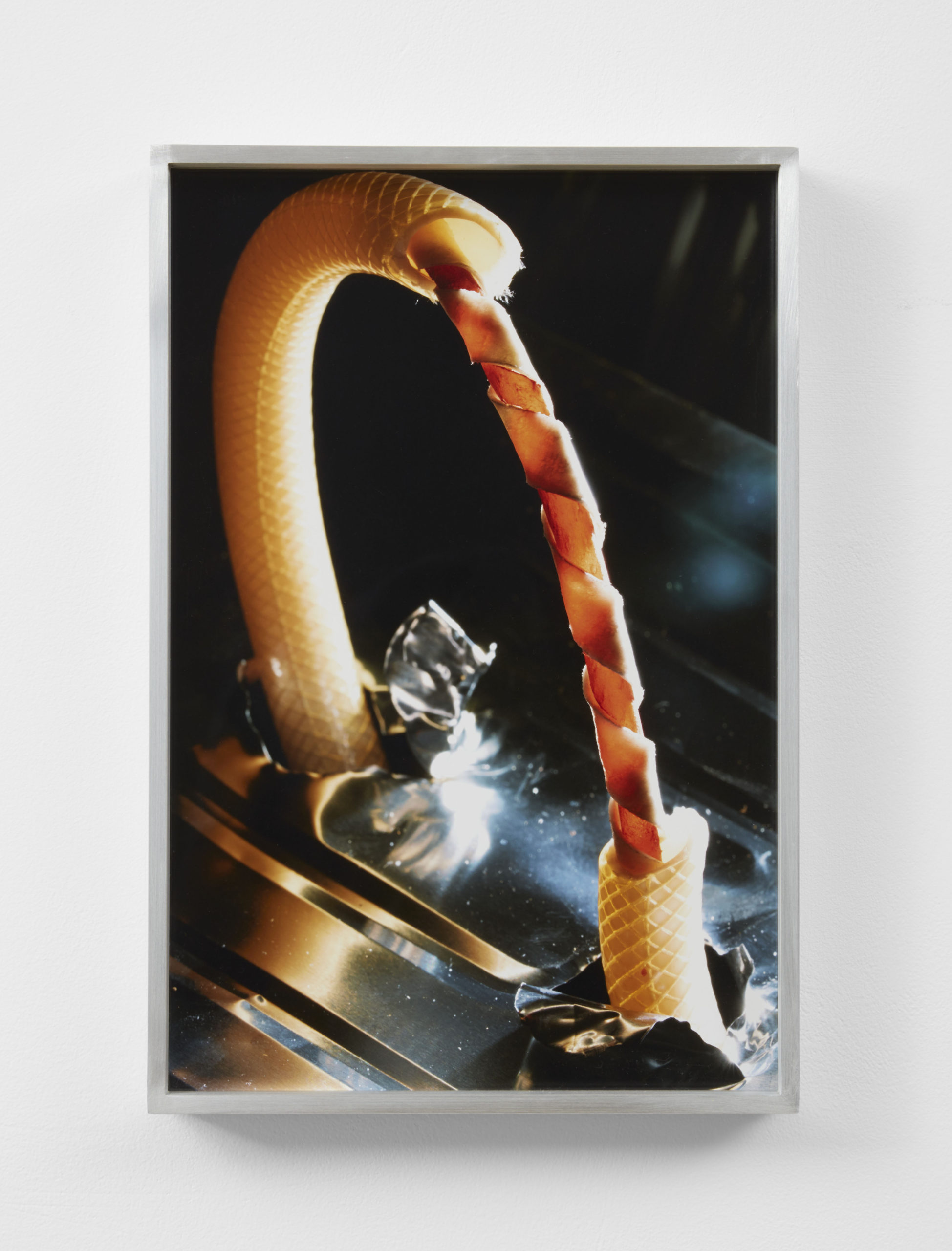

Diane Severin Nguyen’s photographs of visceral sculptural contortions are rich with visual data, yet they conceal her exact methods and source materials. Her photos displaying tactile combinations of unknown substances are most likely a product of deliberate staging, editing, printing and framing. Although we can’t assume that the sumptuous images are representations of what Roland Barthes refers to as photography’s noeme or “that-has-been,” there’s just enough plausibility in Nguyen’s photographs to imply that they might link to something we can know, feel and touch. They are suggestive of trauma, but perhaps only as an idea or visual device. In World Suck (2018) one may observe a translucent tube exuding a heavy teardrop of rubbery liquid, surrounded by glowing orange mass of what appears to be a crumpled film of melting plastic. Is this happening on the “inside” or the “outside?” Is it on fire? Is it bleeding? Should we be alarmed? As Rachel Ossip suggests in her writing on the work of Hito Steyerl, “Images also make worlds.”[3] Nguyen toys with our desire to make stories out of images. By keeping her cards close to the chest, she slyly directs attention away from the artist, and the process, and trains our focus on the evocative viewing experience.

Likewise, Miljohn Ruperto’s short film, The Elusive Nardong Putik (2019), resists the clichéd path to linear narrative in the genre of historical biography. Ruperto playing film director, interviewer, and reluctant subject, constructs a fictionalized portrait of Filipino gangster Leonardo Manicio, better known as Nardong Putik (b. 1925- d.1971). This legendary defender-of-farmers gained his nickname, meaning “mud,” by submerging himself in rice paddies to escape his pursuers. Putik attributed several narrow escapes to his life-preserving amulet, or anting-anting. Though the life story of this anti-hero has been made into two films, Ruperto insists on the impossibility of reconstructing a person’s life in a single narrative, or even more than one. Shot on Super 8 film, the camera holds on the back of a man’s head and shoulders as he walks down a dirt road. The clip is looped; he seems to make no progress. He never turns his head to reveal his face. The voiceover is an interview between the incarcerated Putik and an unknown visitor to his cell. Putik refuses to explain himself to the unseen interviewer, though his glib answers belie a certain willingness to be remembered; the subject is merely resisting what Louis Althusser would call interpolation into an apparatus. Ruperto’s film reminds us that revisionist history requires more than an overlay of updated versions in existing formats. Instead of a new Hollywood biopic, Ruperto’s depiction of Putik enables his fragmentary and fictionalized history to haunt us.

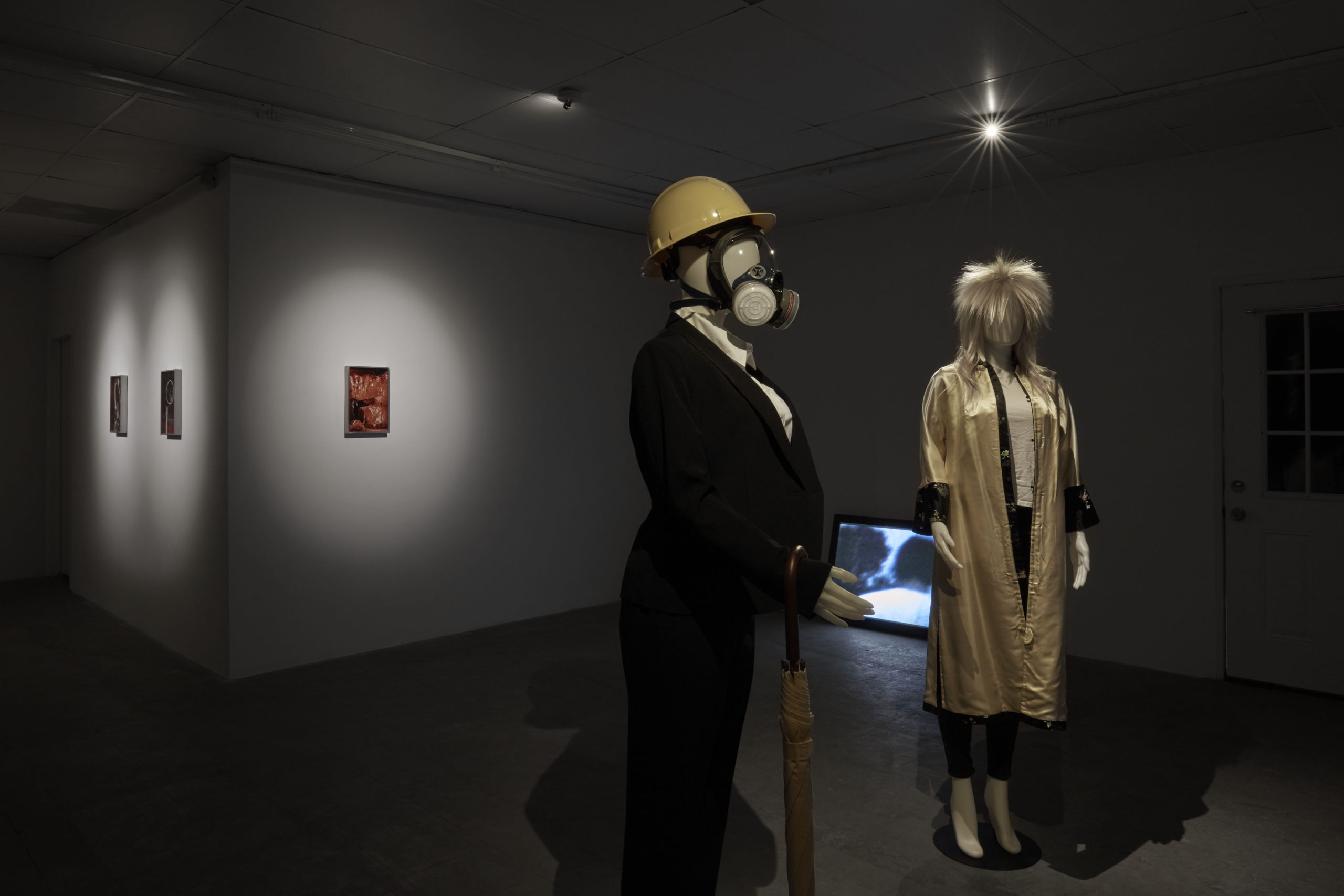

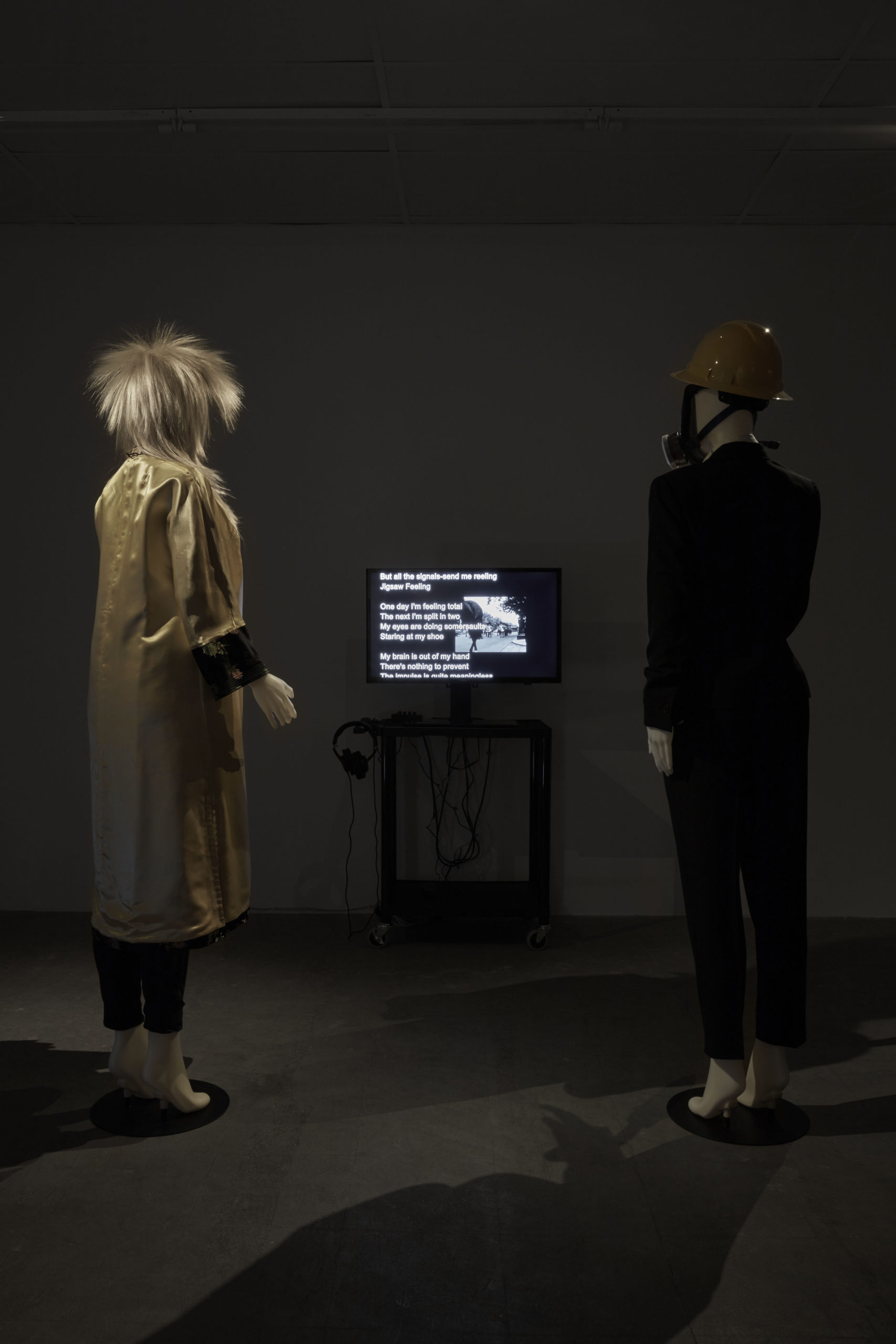

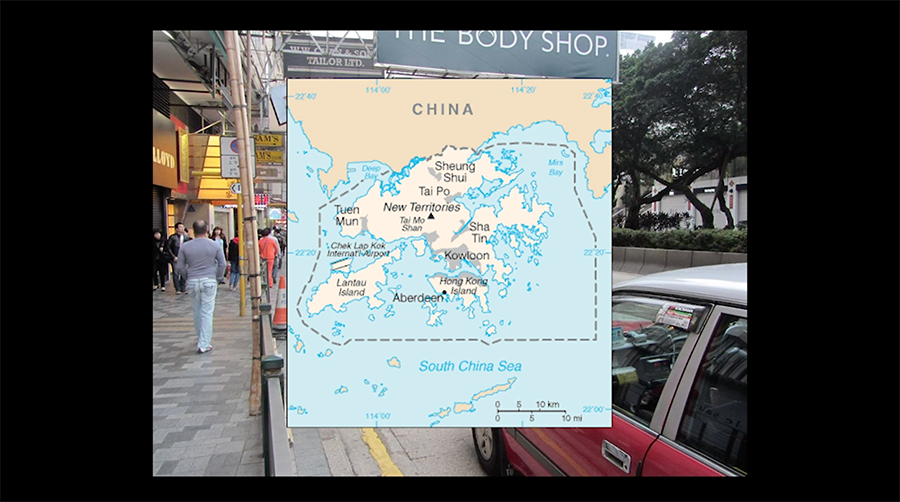

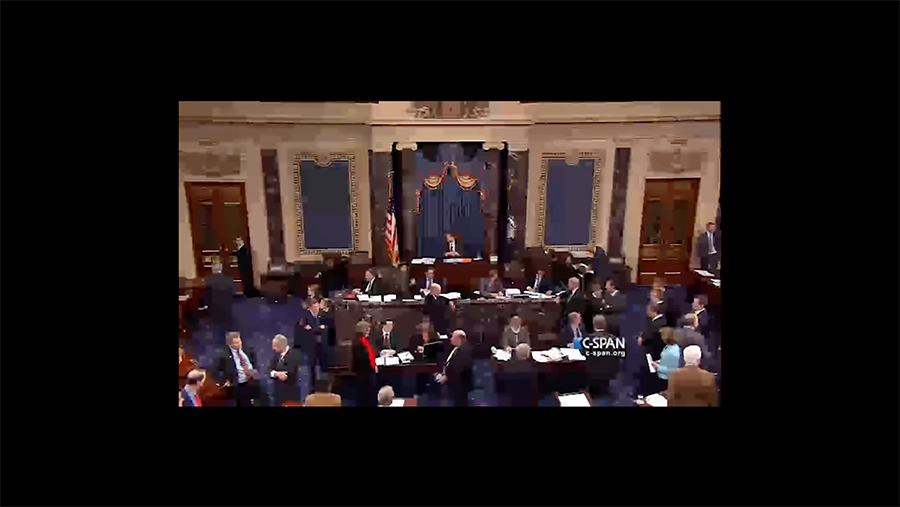

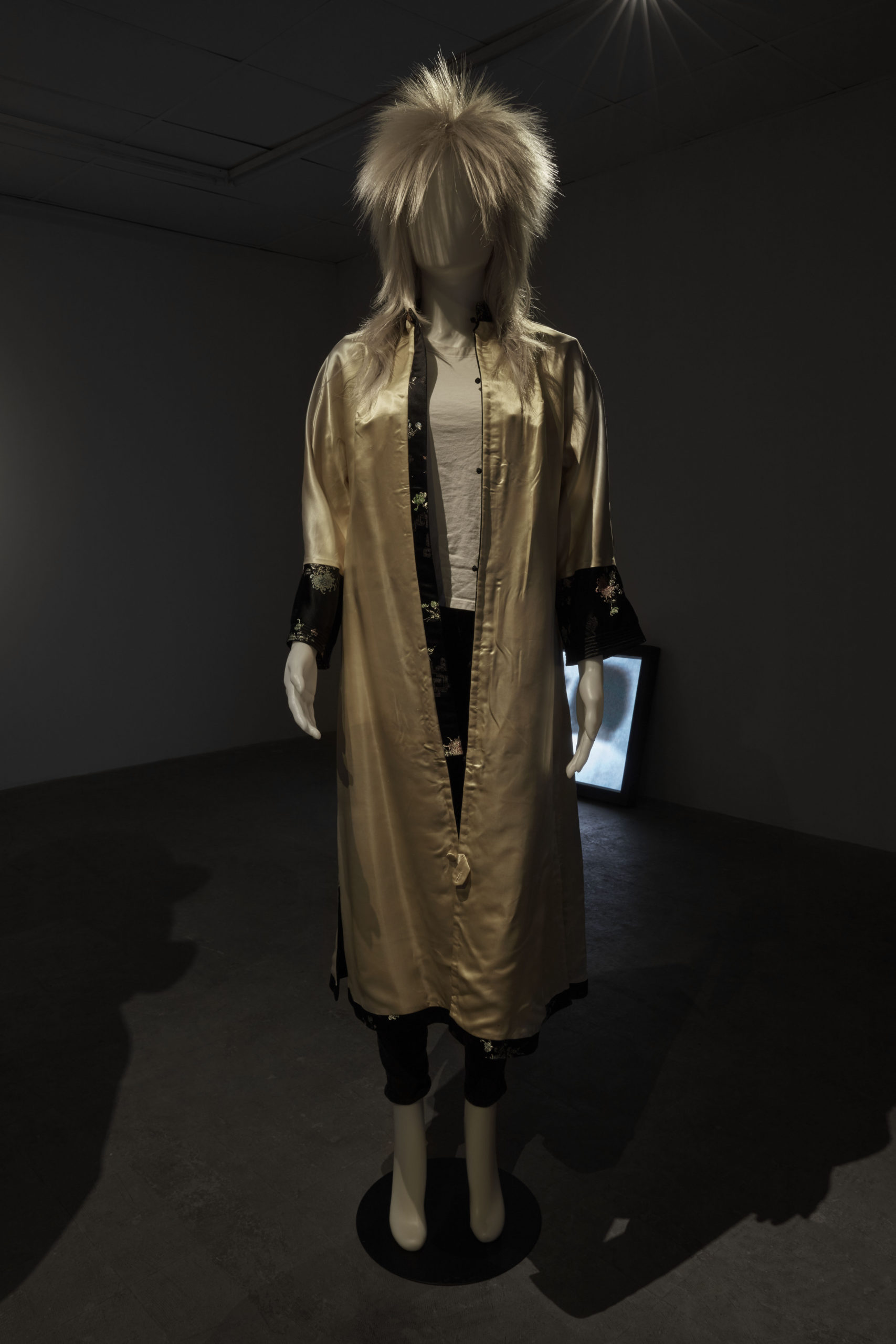

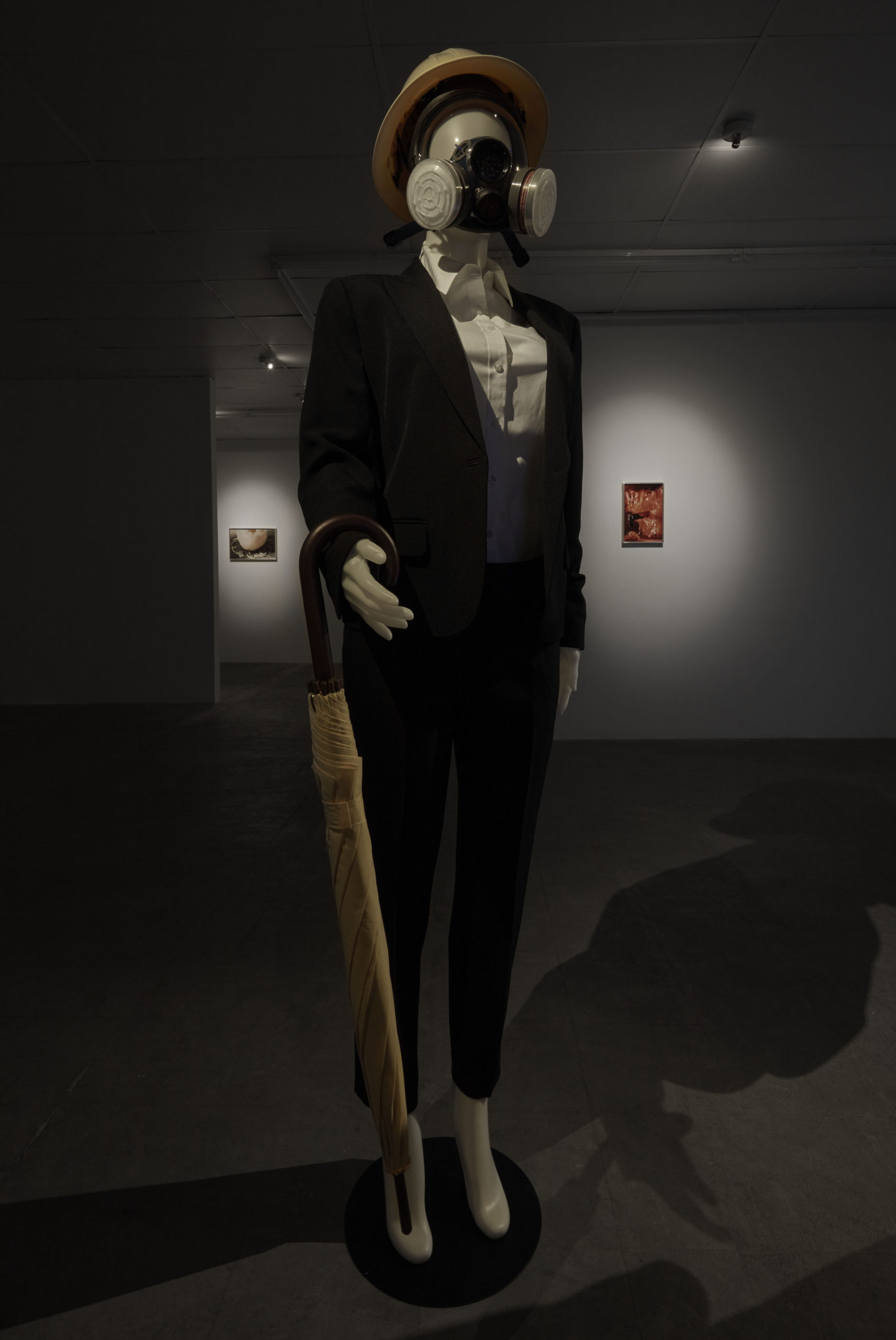

D’Ette Nogle’s new work for this exhibition, Smart Casual (2019), explores the storytelling of current events. Attending to her role as a reader and a watcher, Nogle assembles a story of the Hong Kong protests, escalating since the introduction of the Fugitive Offenders Amendment Bill in March 2019. Using a video accompanied by two mannequins, she moves in and out of her understanding of a cause and its urgency while questioning the legitimacy of her artist-investment. With recognition of the distance between herself and the Hong Kong protesters, Nogle presents the challenge of venturing into the telling of a story shouted out in many voices.

For filmmaker and painter Rosalind Nashashibi, any collectively-told story requires a degree of flexibility and license. The Shobies’ Story by Ursula K. Le Guin prompted her most recent two-part film featuring the artist, her two children and close friends. Nashashibi adopts a non-linear narrative, alternating between domestic interiors and outdoor settings in Lithuania, London and Edinburgh. The film, motivated by Nashashibi’s desire to spend more time with her children, becomes an experiment in imagining forms of community beyond the nuclear family. Nashashibi’s cohort are willing players in this story of casual vacation retreats loosely re-envisioned as an excursion through interstellar space. In Part One, entitled Where there is a joyous mood, there a comrade will appear to share a glass of wine (2018), scenes based on moments in Le Guin’s story are spliced in amongst a scattered discussion about time travel and love. Staged scenes are almost indistinguishable from unplanned occurrences, together creating the film’s unique rhythm. It’s both calm and a little chaotic. In the making of Part Two, entitled The moon is nearly at the full. A team horse goes astray (2019), one guest becomes unexpectedly ill and an ambulance is called; Nashashibi includes this disturbance in the film. While Nashashibi claims a position of authority as the film director, her empathy for her cast and crew of close relations is palpable as she plays roles on both sides of the camera. This extended family of actors mirrors the vulnerability of the crew aboard the Shoby, especially when the eldest player (unnamed) is observed to be silently crying. Death is proximal, perhaps due to the fragmentary nature of the film, and the temporality of a brief seaside vacation during changing seasons. Like in The Shobies’ Story, a crew sets out seeking a new model for co-habitation, and ends up with an ancient yet prosaic one.

Rosalind Nashashibi (b. 1973, Croydon, London) lives and works in London. She studied at Sheffield Hallam University and Glasgow School of Art. Solo exhibitions include: GRIMM, Amsterdam (2020) (forthcoming); S.M.A.K., Ghent (2019) (forthcoming); The High Line, New York, NY (2019); CAAC, Sevilla (2019); Edinburgh Art Festival, Scottish National Gallery Modern Art, Moder One, Edinburgh (2019); Secession, Vienna (2019); GRIMM New York, NY (US)(2019); Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw (2018); Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam (2018); The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (2018); Introduction, PM8 Galería, Vigo (2018); Murray Guy, New York, NY (2016); Imperial War Museum, London (2015); and Objectif Exhibitions, Antwerp, Netherlands (2013). Selected group exhibitions include: Cinéma du Réel, Centre Pompidou and Forum des Images, Paris (2019); Annunciations, M. LeBlanc, Chicago, IL (2018); Inky Protest, Peacock Visual Arts & Nuart Gallery, Aberdeen (2018); Turner Prize, Tate Britain, London (2017); Being Infrastructural, Mother’s Tank Station, Dublin (2017); Documenta 14, Kassel (2017); I Call This Progress to a Halt, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA (2017); Ghost of Other Stories, British Council Collection at The Model, Sligo (2016); Corps Simples, Centre Pompidou, Malaga (2015); Sudoku, Kunstverein München, Munich (2015); A Million Lines, Baltic Triennial, Bunkier Sztuki, Krakow, Poland (2015); and Ten Thousand Wiles and a Hundred Thousand Tricks, Contemporary Image Collective, Cairo (2014).

Diane Severin Nguyen (b. 1990, Carson, CA) lives and works between Los Angeles and New York. She received her MFA from Bard College, Annandale-On-Hudson, NY in 2019, and holds a BA from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA (2013). Selected exhibitions include Empty Gallery, Hong Kong (2019) (forthcoming); A Fickle Aggregate, Chen’s World, Brooklyn, NY (2019); Dead Slow, Exo Exo, Paris, FR (2019); Minor twin worlds, Bureau, New York, NY (2019); and Flesh Before Body, Bad Reputation, Los Angeles, CA (2019). Her work has been reviewed in Objektiv, CURA, X-TRA, Hyperallergic, and AnOther Magazine.

D’Ette Nogle (b. 1974, La Mirada, CA) lives and works in Los Angeles. She received her MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles, CA (2000) and holds a BA in communications from Chapman University, Orange, CA (1997). Recent solo exhibitions include Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles, CA (2019); Bodega, New York, NY (2019); Reserve Ames, Los Angeles, CA (2016). Recent group shows include Gallery Share hosted by Hannah Hoffman, Kristina Kite Gallery, and Park View, Los Angeles, CA; Hurts to Laugh, Various Small Fires, Los Angeles, CA (2018); A Change of Heart, Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles, CA (2017); EGG, Essex Street, New York, NY (2015). Her work has been featured in Made in L.A. at The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA (2012) and Sonsbeek 9, Arnhem (2001).

Miljohn Ruperto (b. 1971, Manila) lives and works in Los Angeles. He received his MFA from Yale University, New Haven, CT in 2002 and his BA in studio art from University of California, Berkeley, CA in 1999. Ruperto has exhibited his work internationally at numerous venues, including Geomancies, REDCAT Gallery, Los Angeles, CA (2017); What We Know that We Don’t Know, Kadist, San Francisco, CA (2017); Afterwork, ILHAM Gallery, Kuala Lumpur (2016–17) and Para-Site, Hong Kong (2016); Nervous Systems, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin (2016); 2014 Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2014); Made in L.A., Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA (2012). Ruperto is represented by Koenig & Clinton, Brooklyn, NY.

[3] Ossip, Rachel. “Ghost World.” n+1, 2018, nplusonemag.com/issue-32/reviews/ghost-world/

Miljohn Ruperto

The Elusive Nardong Putik, 2019

8 mm film transferred to digital video

7 min 2 sec

D’ette Nogle

Smart Casual, 2019

single-channel video, mannequins, black suit, white-collared shirt, hard hat, gas mask, umbrella, satin coat, t-shirt, jeans, blonde wig, TV, media cart, headphones

dimensions variable, video duration: 33 min 26 sec

Rosalind Nashashibi

Part one: Where there is a joyous mood, there a comrade will appear to share a glass of wine, 2018

16 mm film transferred to digital video

23 min 53 sec

Rosalind Nashashibi

Part two: The moon is nearly at the full. A team horse goes astray, 2019

16 mm film transferred to digital video

21 min 21 sec

Diane Severin Nguyen

World Suck, 2018

LightJet C-print, aluminum frame

15 × 10 in (38.1 × 25.4 cm)

Diane Severin Nguyen

Reversible Destiny, 2019

LightJet C-print, aluminum frame

15 × 10 in (38.1 × 25.4 cm)

Diane Severin Nguyen

Hybrid Perpetual, 2018

LightJet C-print, aluminum frame

15 × 10 in (38.1 × 25.4 cm)

Diane Severin Nguyen

An era where war became a memory, 2018

LightJet C-print, aluminum frame

15 × 10 in (38.1 × 25.4 cm)

D’ette Nogle

Smart Casual, 2019

video: 33 min 26 sec